|

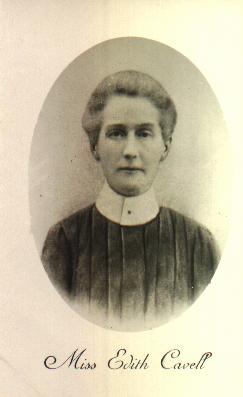

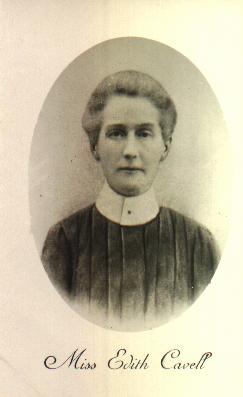

Edith Louisa Cavell

(4 December 1865–12 October 1915)

(Above) Matchsafe examples, showing Edith Cavell

She was a victim of Teutonic "Kultur" (culture) - a word engraved on this trench art letter opener, together with a German picklhaube (Below)

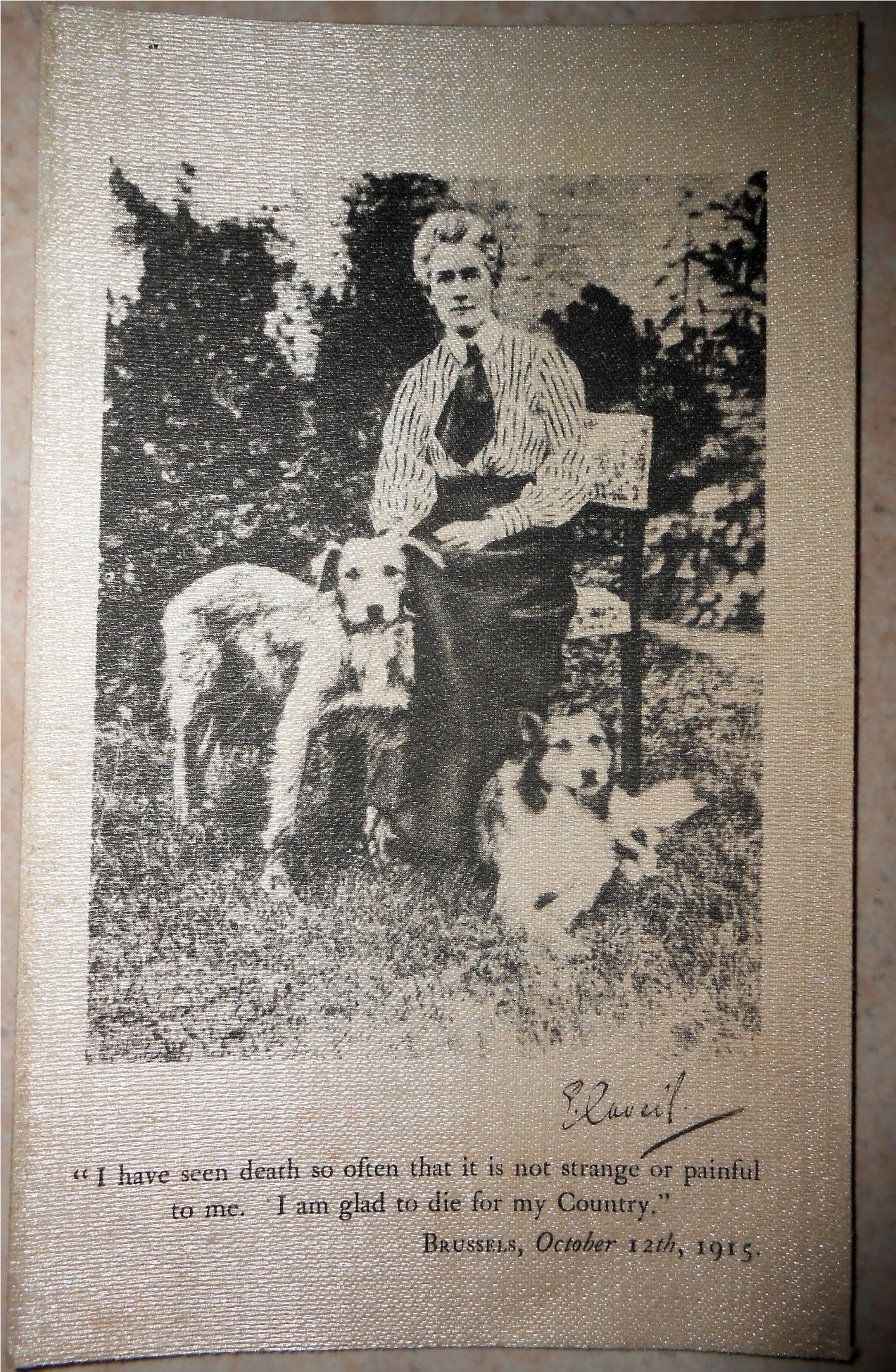

"Patriotism is not enough, I have no fear or shrinking; I have seen death so often it is not strange, or fearful to me..."

(Above) Edith Cavell's statue in London (recent), unveiled by Queen Alexandra in March 1920 (Below)

Edith Cavell was born in a temporary vicarage in Swardeston, near Norwich, England, where her Father was employed as an Anglican Priest.

Aged 16, she went to boarding school in Kensington, afterwards Clevedon, then Laurel Court, Peterborough, learning to become a pupil teacher and acquiring French as her second language.

When 21, she became a family governess to the Vicar's children in Steeple Bumpstead, Essex, and then, for a short period, Governess to the Gurney children at Keswick New Hall, in the next village.

At 23, she was bequested a small legacy; deciding to use these monies to widen her horizons, she travelled to Europe....in Austria and Bavaria, she came upon a "free" hospital run by a Doctor Wolfenberg. Impressed with their works, she endowed the hospital with part of her legacy... she had developed a growing interest in nursing !..........

Aged 25, she became Governess to a Brussels Family.....

Summer breaks were taken in Swardeston (where she formed a romantic attachment to her second cousin Eddie).

In 1895, Edith's Father was ailing - she cared for him - and this experience convinced her that a career in nursing was her destiny. The following April, 1896, after a few months of assesment at the Fountains Fever Hospital, Tooting, she joined the Royal London Hospital to train.

In 1897 typhoid broke out in Maidstone, Kent. Edith went with 5 nurses to aid and assist - she was awarded Maidstone Medal for her dedication to help the epidemic sufferers.

During 1898, as a private nurse, Edith Cavell dealt "hands-on" with such cases of pleurisy, pneumonia and typhoid.

Between 1899 and 1903, Edith worked with destitutes, becoming an

assistant matron at Shoreditch infirmary, pioneering follow-up home visits for discharged patients, and at night, working as a Night Supervisor at the Poor Law institution of St. Pancras Infirmary.

In 1903, Edith became matron at Shoreditch infirmary where she pioneered follow-up home visits for discharged patients. She spent time at Manchester and Salford Sick Poor and Private Nursing Institution and the Queen's District Nursing Homes.

In 1907, she returned to Belgium, to be appointed as matron of a nursing school, L'École Belge d’Infirmières Diplômées (Surgical Institute of Brussels) on the Rue de la Culture in Brussels. By the time she was 50, she had become a training nurse for 3 hospitals, 24 schools, and 13 kindergartens in Belgium.

At the outbreak of World War 1, she was visiting her widowed mother in England. Upon hearing the news of war, Edith came back to Brussels, discovering the school had been taken over by the Red Cross, where she gave her services freely to the care of wounded German soldiers.

Whilst in England, the British Secret Intelligence Service is said to have tried to recruit Edith as their agent, but to be a "spy" was not in her nature - instead she joined an escape network organized by Belgians in the region of Mons and the French from the region of Lille, to aid and assist Allied soldiers travel to safety in neutral Holland. She used a password of the network - "Yorc", an anagram of 'Croy' (from the name of Princess Maria of Croÿ family)

With help from Prince Reginald de Croy, near Mons, needy troops were provided with false identification documents. Some stayed briefly at her house in Brussels before departing, using Guides provided by one Phillipe Baucq, and with sufficient funds, to attempt to reach reach the Dutch Frontier.

De-classified files from the Belgian Government have now revealed testimonies from eyewitness accounts signed in 1920, that there was some espionage carried out by Belgian men and women in the Cavell organisation,

who used traditional spycraft methods, having been recruited as agents. However, British military intelligence has never acknowledged that Edith was one of their agents, and MI6 still do so today.

The Germans were well aware that large numbers of fugitive soldiers were crossing the Belgian border into Holland. Then, in August 1915, the Germans raided Philippe Baucg's home, and arrested him. Unfortunately Baucq failed to destroy several incriminating letters in which Edith Cavell's name appeared.

On August 5, Otto Mayer of the German Secret Police arrived in the Rue de la Culture. Cavell was driven to police headquarters and questioned. But nothing of importance was found in the Institute -- Cavell had, in fact, sewn her diary inside a cushion. Although more than 200 troops had passed through her hands, the only document incriminating the nurse was a tattered postcard sent, rather unwisely, by an English soldier thanking her for helping him to reach home.

Betrayed by one Georges Gaston Quien, who had been one of the Cavell network's couriers, but was in fact a German agent, the German military rounded up Edith and 35 members of the organisation. She was arrested and charged with Treason, (harbouring Allied soldiers). Held in St Gilles prison for 10 weeks, the last two in solitary confinement, she made three depositions, admitting that she had been instrumental in conveying about 60 British and 15 French derelict soldiers and about 100 French and Belgians of military age to the Dutch frontier bound for England, and had sheltered most of them in her house.

A secret court prosecuted her for "conducting soldiers to the enemy".

Admitting her "guilt" she'd previously signed a statement to the effect that some men she had helped had thanked her in writing when arriving safely in Britain. (However, she'd been questioned in French, but the interview was "minuted" in German. (This gave the interrogator the opportunity to misinterpret her answers.) Although she may have been misrepresented, she made no attempt to defend herself.

This statement reaffirmed the alleged "crime" in the eyes of the court - that she had been complicit in helping enemy soldiers "escape" to a Country at war with Germany. In accord with German military law (supported by the First Geneva Convention), the sentence was "death for treason".

26 members of her organisation were found guilty, and 5 received the death penalty (later commuted to life imprisonment, except for Edith and Philippe Baucq).

Much controversy followed, with the British Government stating they could do nothing to help Edith. The First Secretary of the United States Legation at Brussels, Hugh Gibson, made it clear to the German Government that any execution would further harm their already damaged reputation.

German civil governor, Baron von der Lancken, stated that Edith should be pardoned because of her complete honesty and that she had helped save so many lives, German as well as Allied.

However, General von Sauberzweig, the military governor of Brussels, ordered that "in the interests of the State" the execution of the death penalty should be carried out immediately, thus denying higher authorities the opportunity to consider clemency. The sentence was passed at 5:00 pm on 11th. October, and carried out nine hours later.

Four hours before her execution, Edith told the British Chaplain at Brussels, Rev. Stirling Gahan, an Anglican Chaplain who had been permitted to enter her prison cell to offer Holy Communion, "Patriotism is not enough, I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone. I willingly give my life for my Country, and I have no fear nor shrinking; I have seen death so often that that it is not strange or fearful to me".

These words are inscribed on her statue in St Martin's Place, near Trafalgar Square in London (pictured above). Her final words to the German Lutheran prison chaplain, Paul Le Seur, were recorded as:

"Ask Father Gahan to tell my loved ones later on that my soul, as I believe, is safe, and that I am glad to die for my Country."

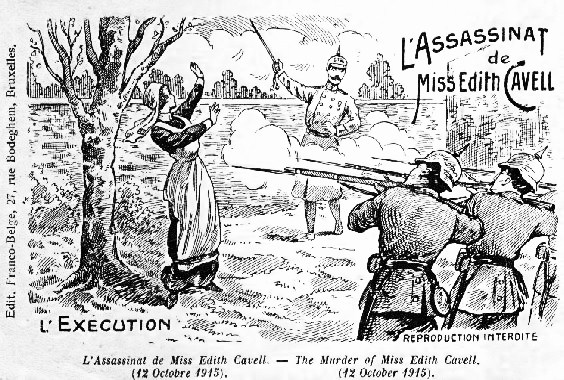

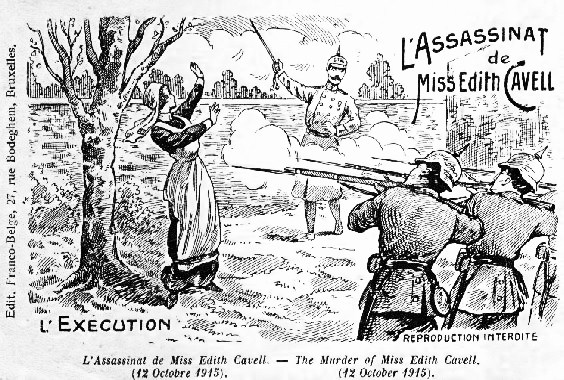

Despite appeals for mercy, or a postponement of sentence to German authorities, of whom the chief was Baron von der Lancken, head of the Political Department and the Military Governer, who had personally received clemency appeals from Spain and the United States up until midnight on the 11 October, Edith was executed by firing squad, together with Philippe Baucq at Tir National shooting range in Schaerbeek two hours later, at 2:00 am on 12 October 1915, an act the World viewed as one of German barbarism and moral depravity.

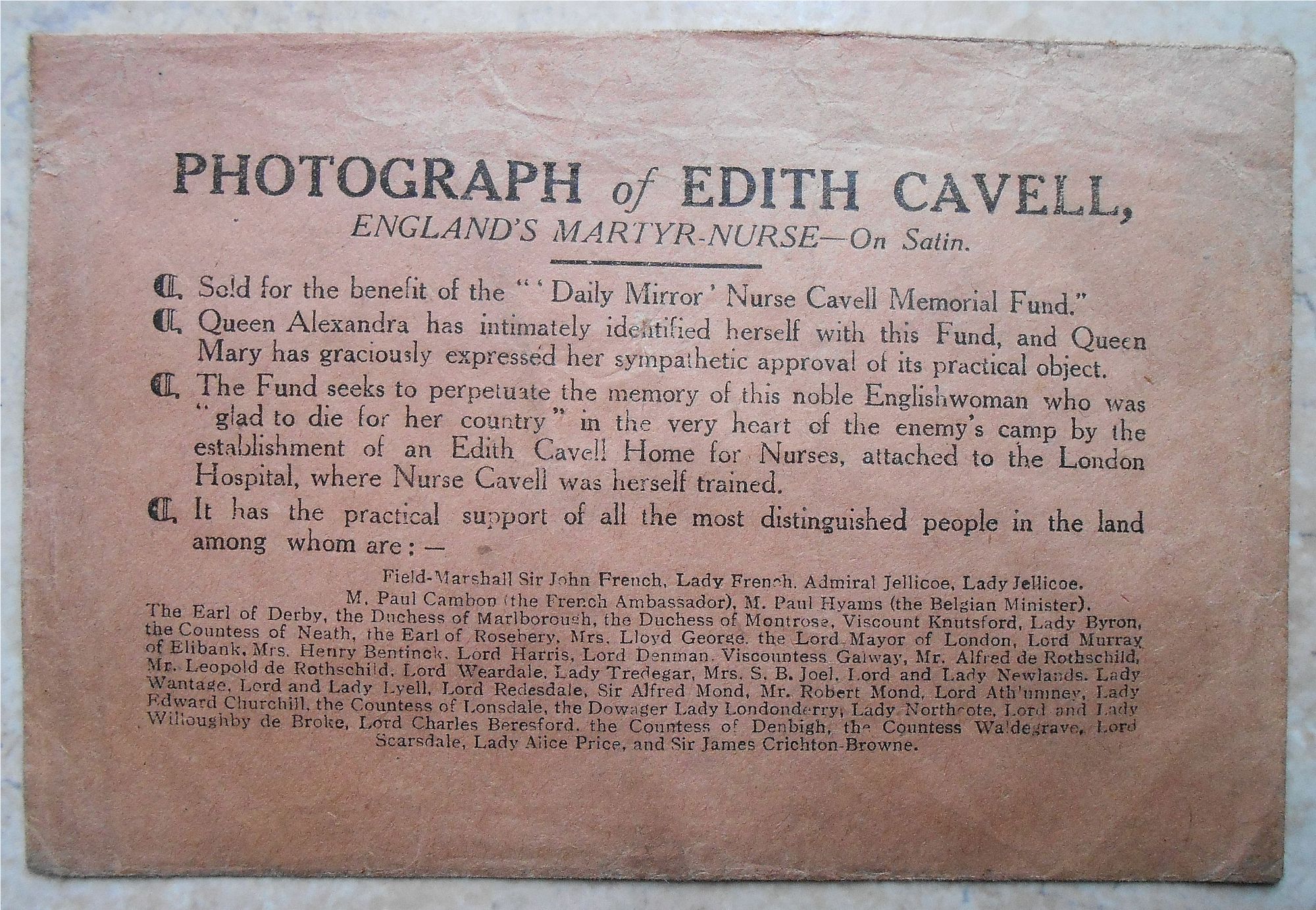

(above) Postcard image - a fictional viewpoint, to enrage emotion - (below) the Execution Stool where the actual murder was committed by Germany (with an onlooker !)

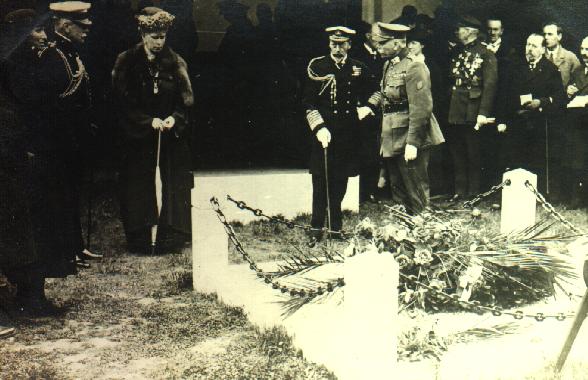

After her execution, Edith's body was buried in a desolate patch of wasteland next to the Tir National, the Belgian national shooting centre used by the Germans for executions - a simple white wooden cross marked her resting place. After the war, her body was repatriated to England where she was given a state funeral in Westminster Abbey, before being reburied in Norwich Cathedral.

(Above) Sailors bear Cavell's coffin as her remains are returned to the UK in May 1919.

It was the deliberate intention of the German authorities to exact the death penalty because Miss Cavell was an Englishwoman. As Sir Edward Grey wrote at the time: "News of the execution of this noble Englishwoman will be received with horror and disgust , not only in the Allied States, but throughout the civilised world. Miss Cavell was not even charged with espionage, and the fact that she had nursed numbers of German Soldiers might have been regarded as a complete reason in itself for treating her with leniency".

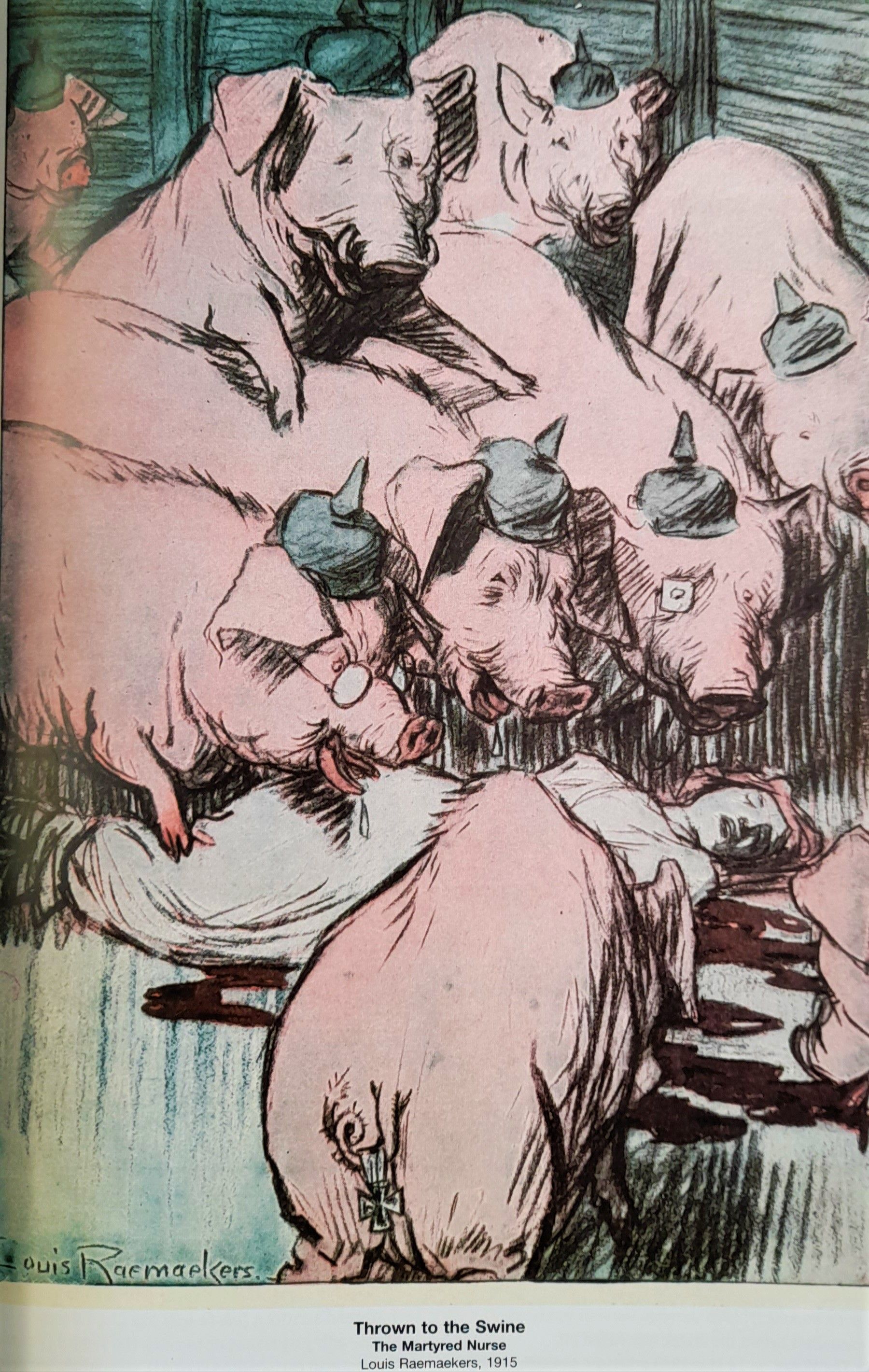

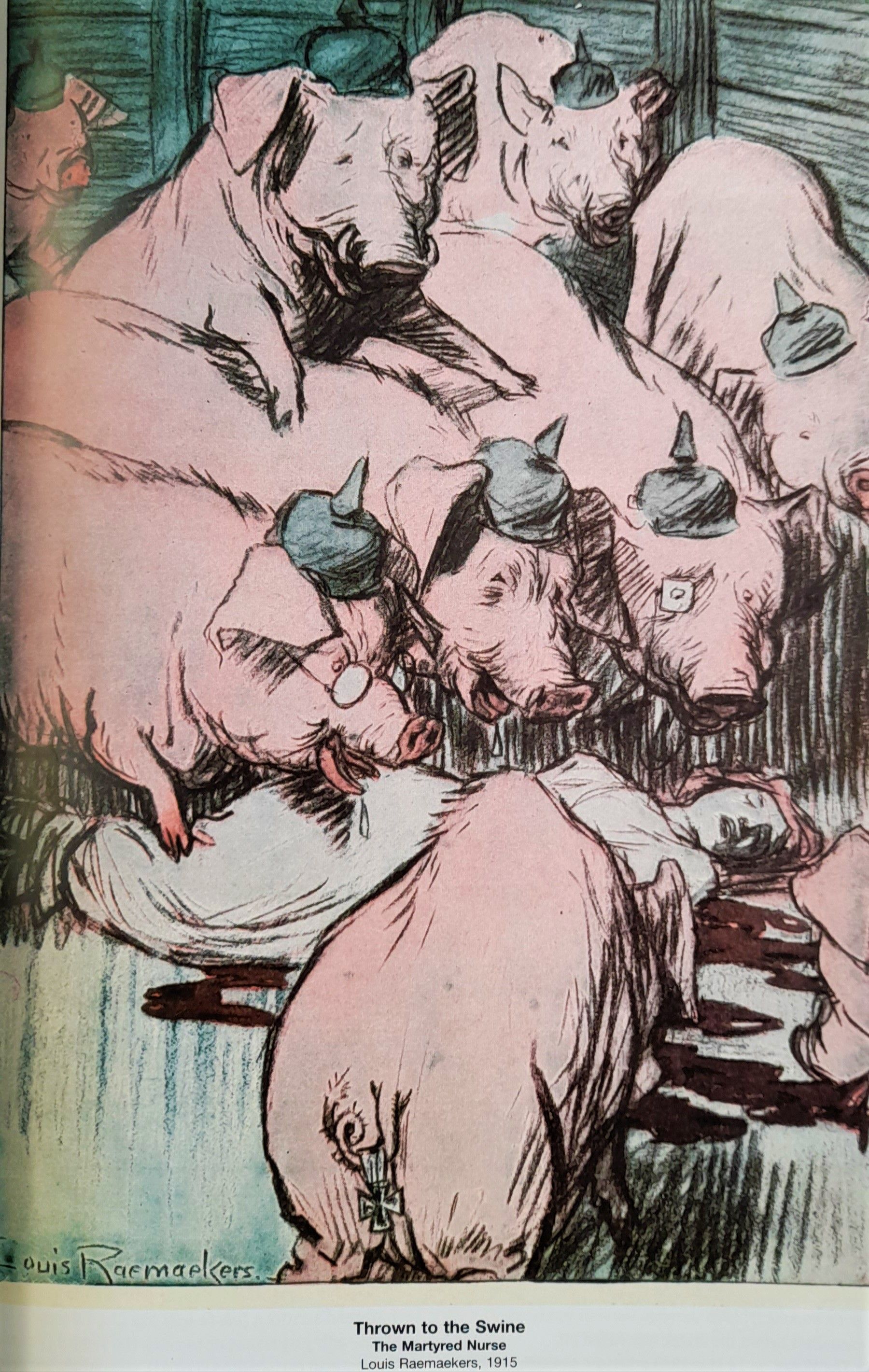

Edith Cavell's life and death became a powerful propoganda subject for the British Government, helping military recruitment in Britain, and gaining favourable sentiment towards the Allies, in the neutral United States.

(above) Photo of Edith Cavell's grave at Norwich Cathedral, taken on 12/10/2015, 100 years after her death, by David Cason.

(Above) £5 British Coins (left Gold proof) (right Silver proof)

(Above) $1 British Virgin Islands Coin

Propaganda cartoon, showing pigs devouring Edith Cavell. They wear German picklehaubes and the nearest one has a German Iron Cross on its tail.

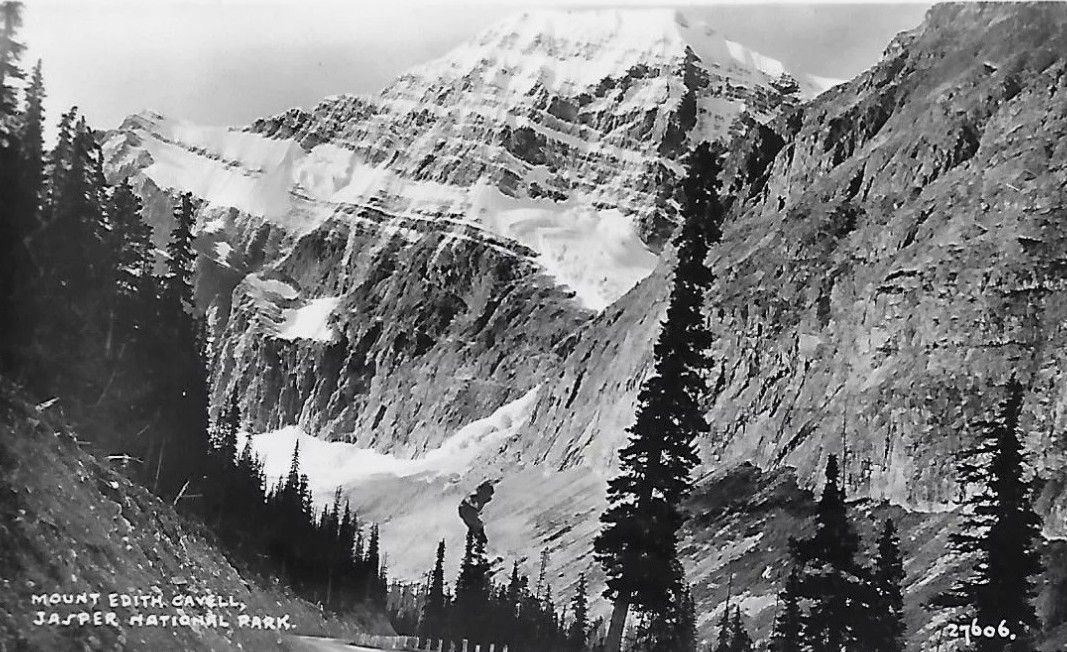

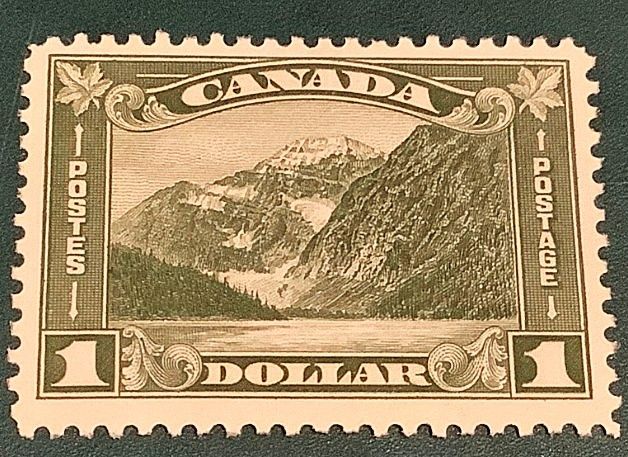

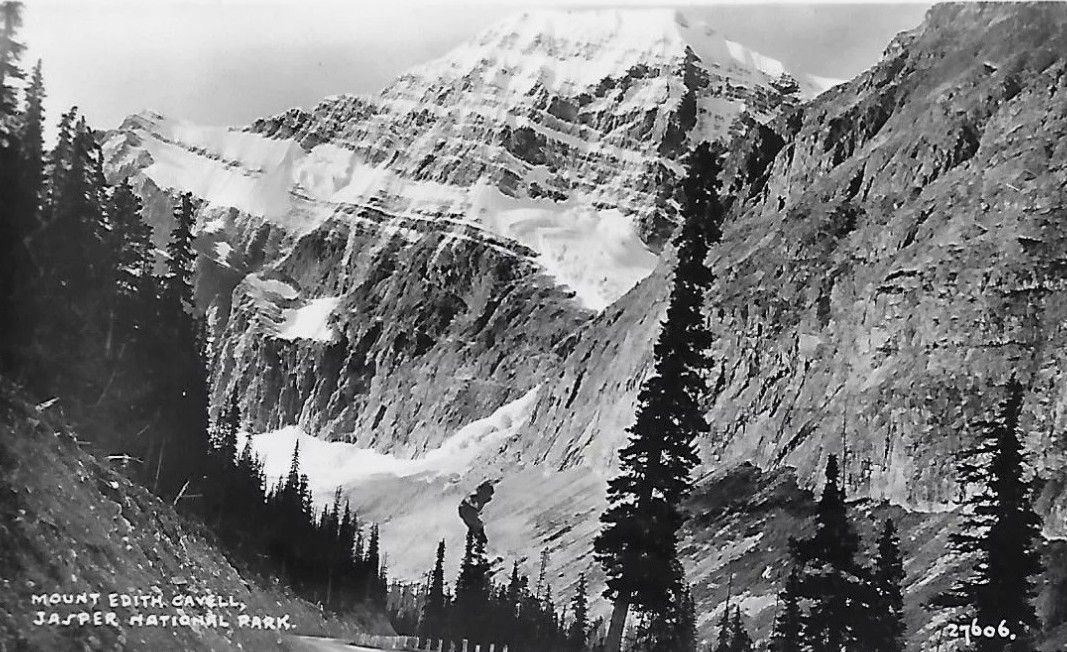

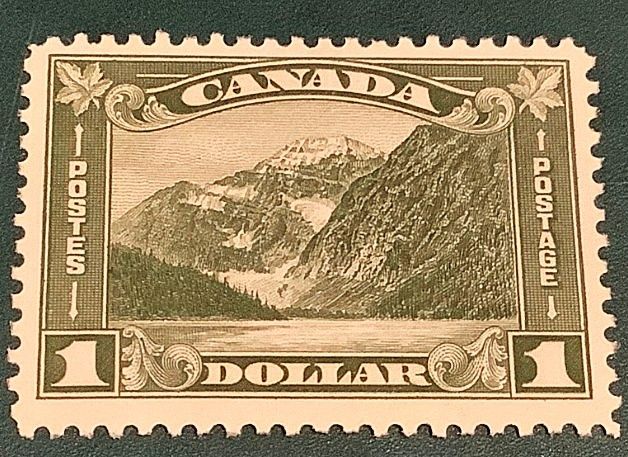

MOUNT EDITH CAVELL, CANADA.

|

|