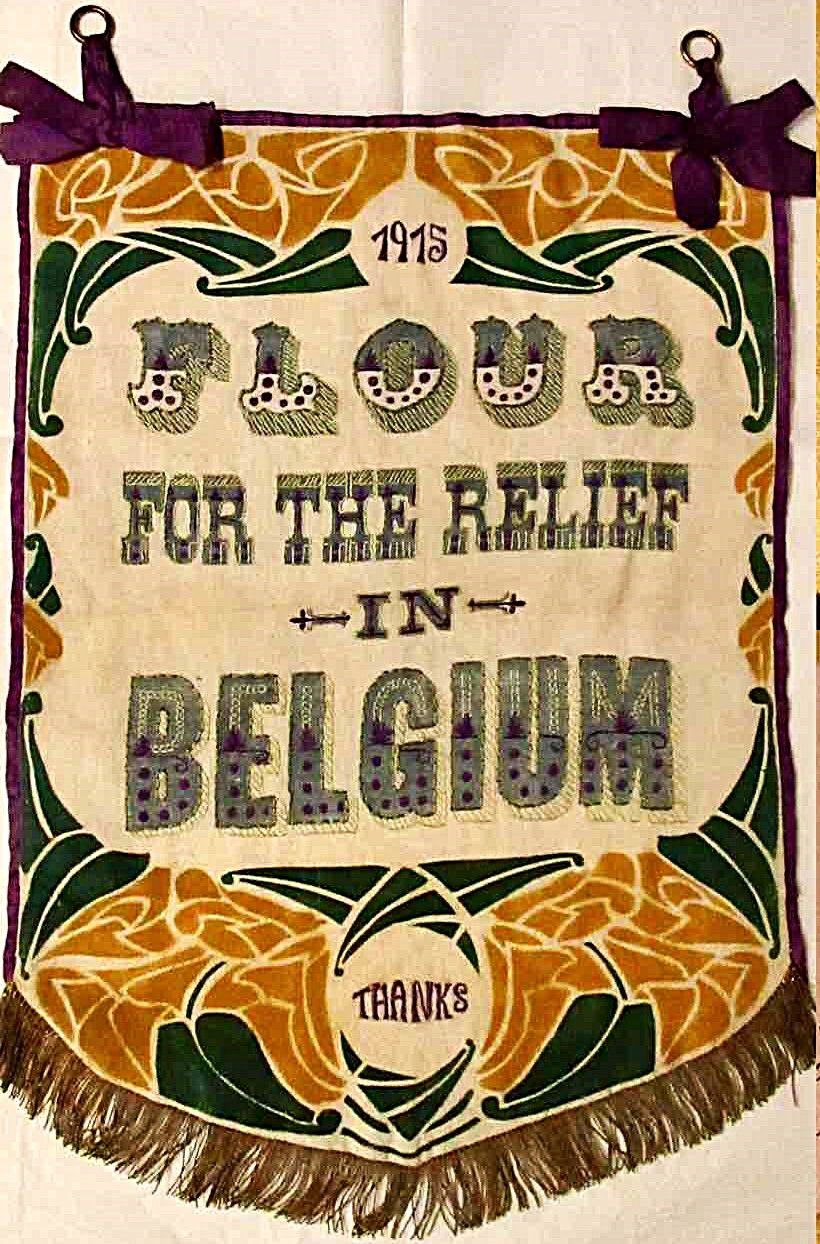

FLOUR SACK ART

(every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyrighted material. I apologise for any errors or omissions and would be grateful to be notified of any objections to the image(s) shown.

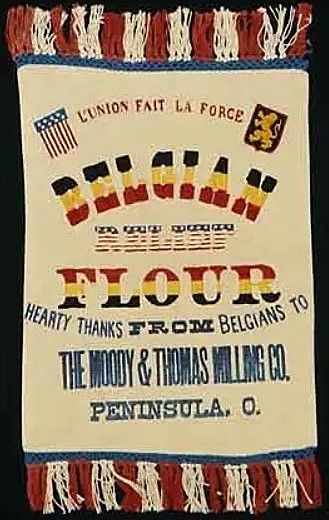

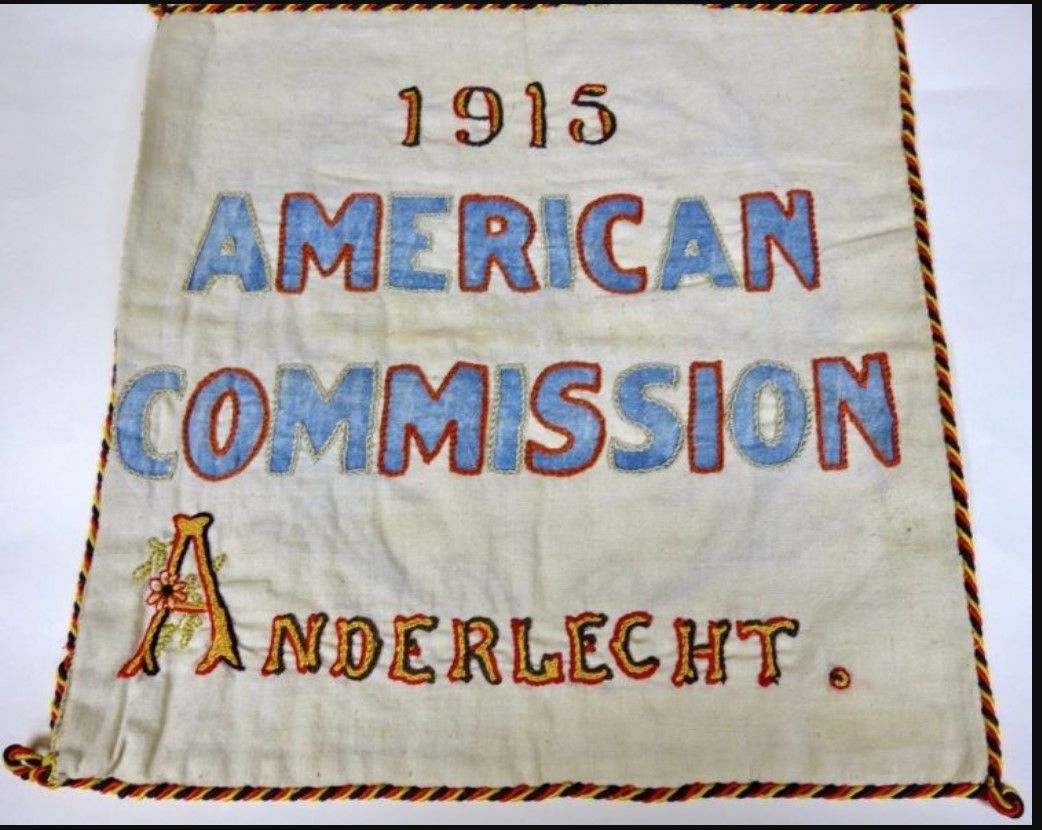

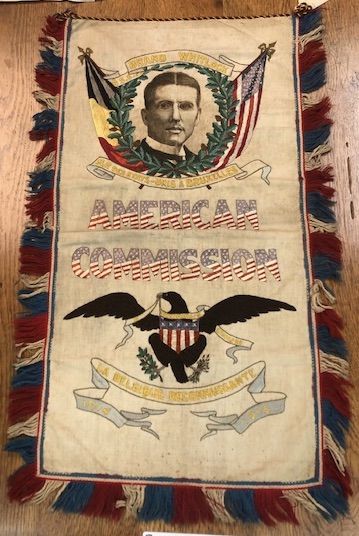

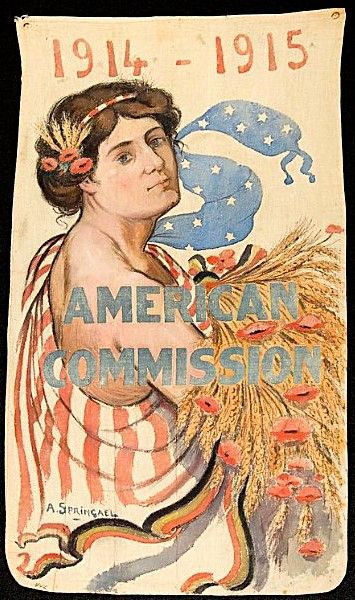

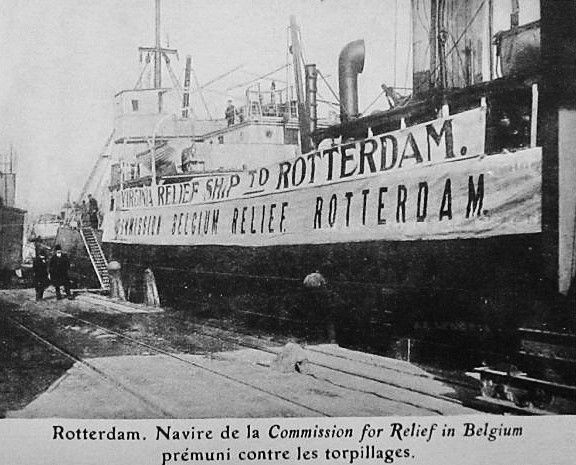

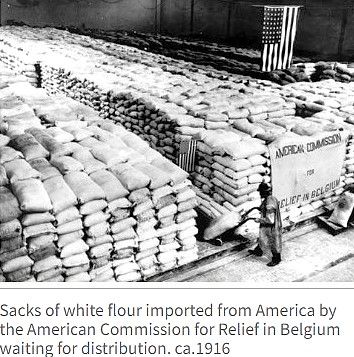

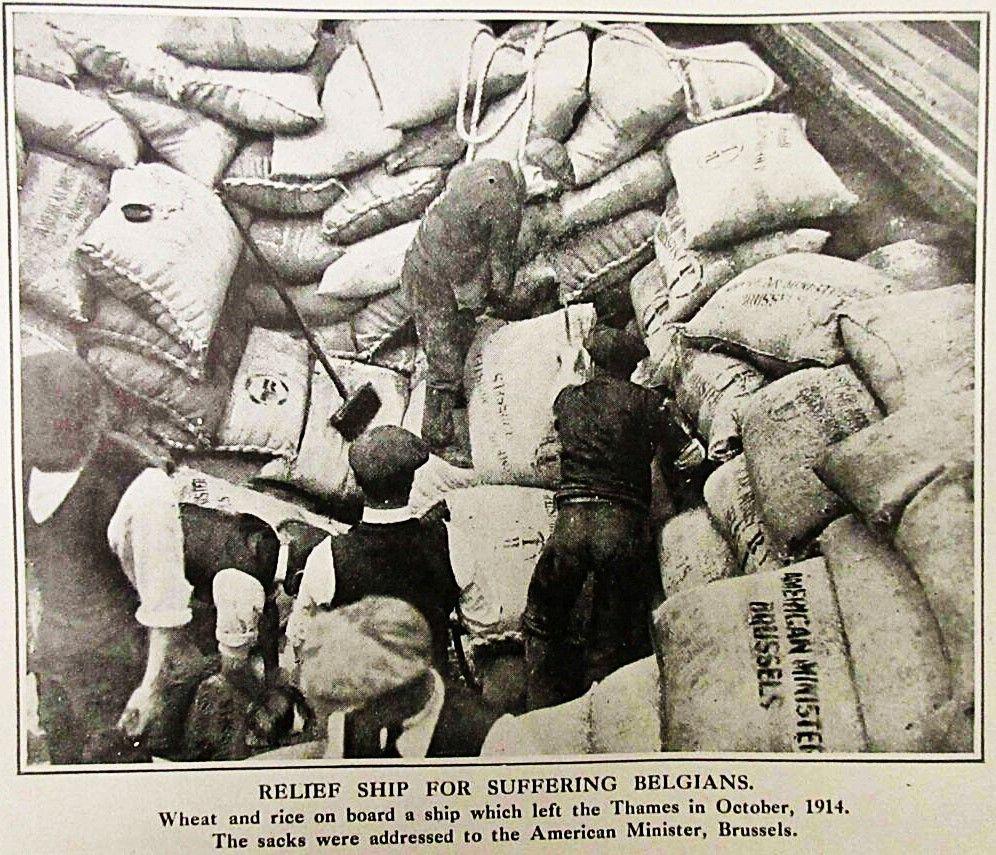

In October 1914 the American Commission For Relief in Belgium (CRB) was set up under the chairmanship of Herbert Hoover, later the 31st President of the USA, to provide food relief in Belgium.

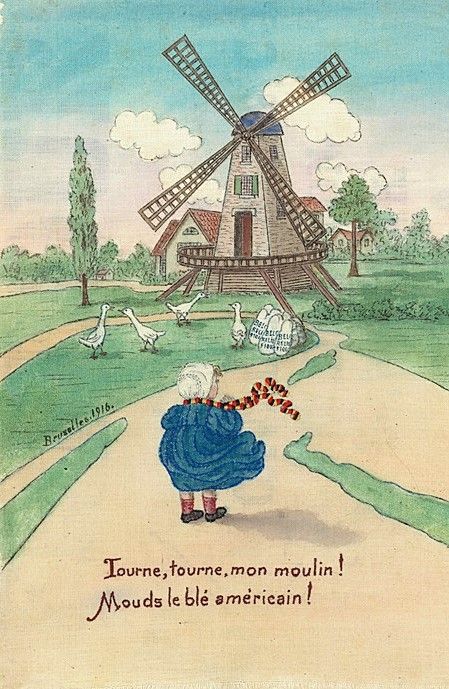

Belgium suffered terribly during World War I. One major cause of suffering was the lack of provisions. The Belgians normally imported most of their food. When Germany invaded in the summer of 1914, its soldiers confiscated foodstuffs and then refused to feed the populace. Meanwhile, Great Britain set up a naval blockade halting all imports. By the winter of 1914-1915, it was clear Belgians would starve unless they received outside assistance. Although the United States remained neutral until the war's final year, American citizens got involved in a major relief effort run by Herbert Hoover.

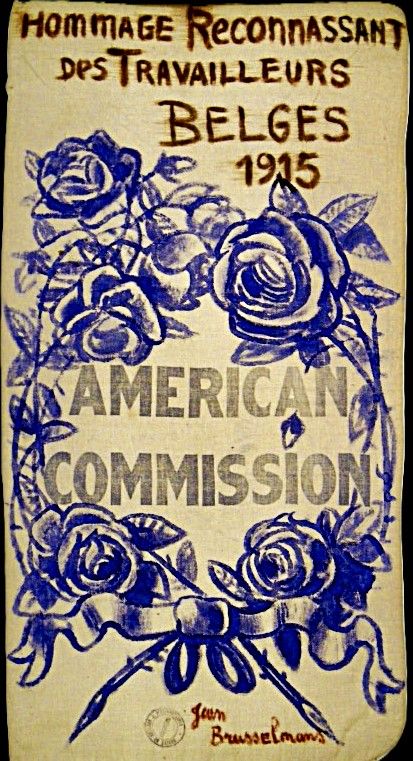

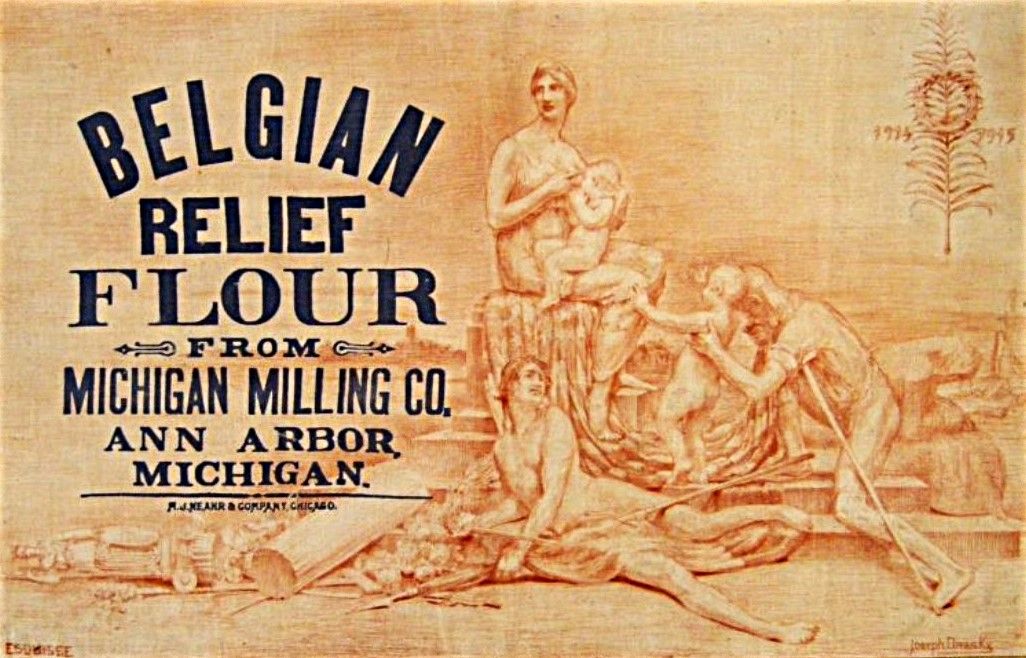

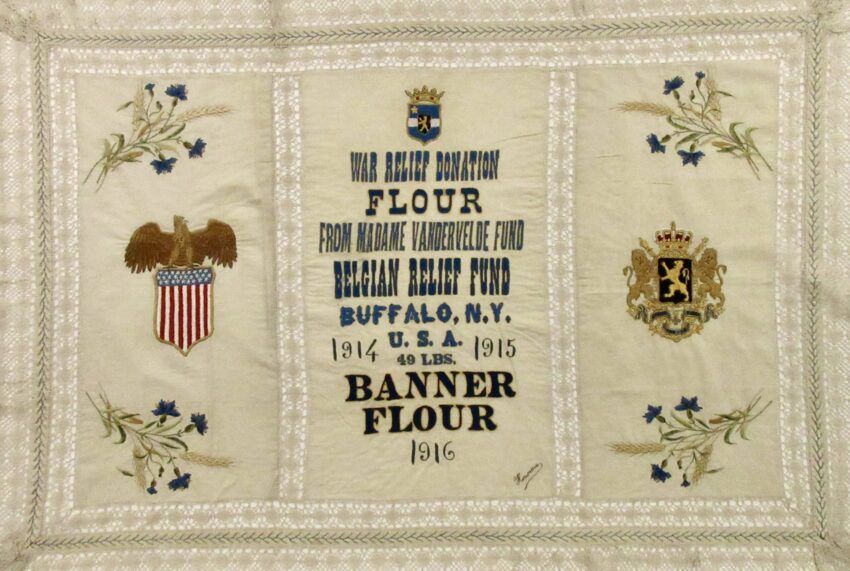

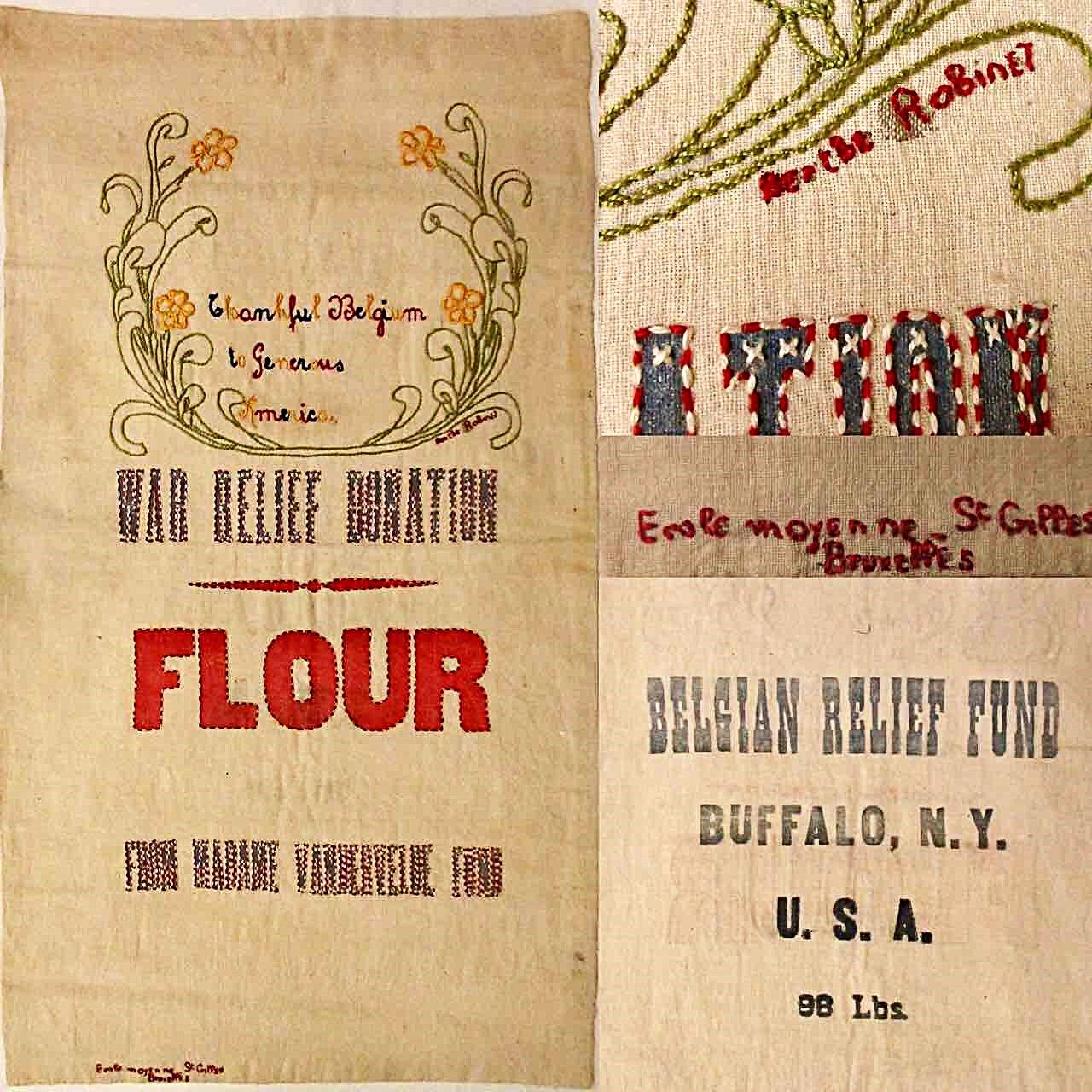

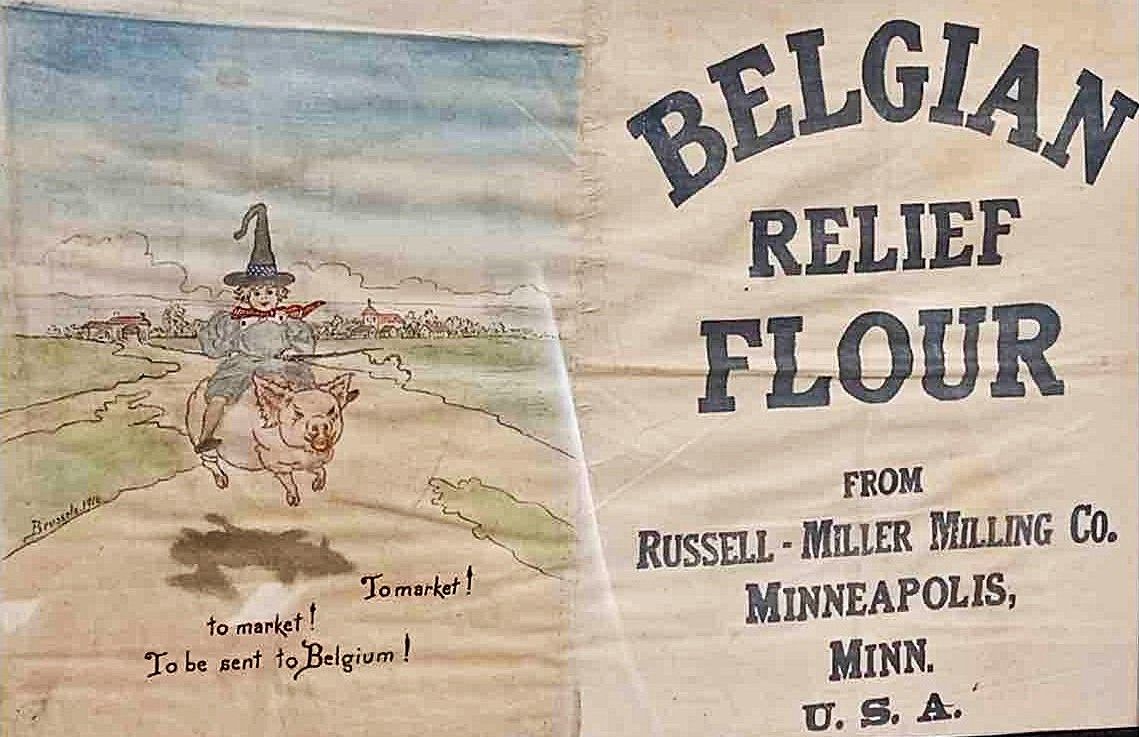

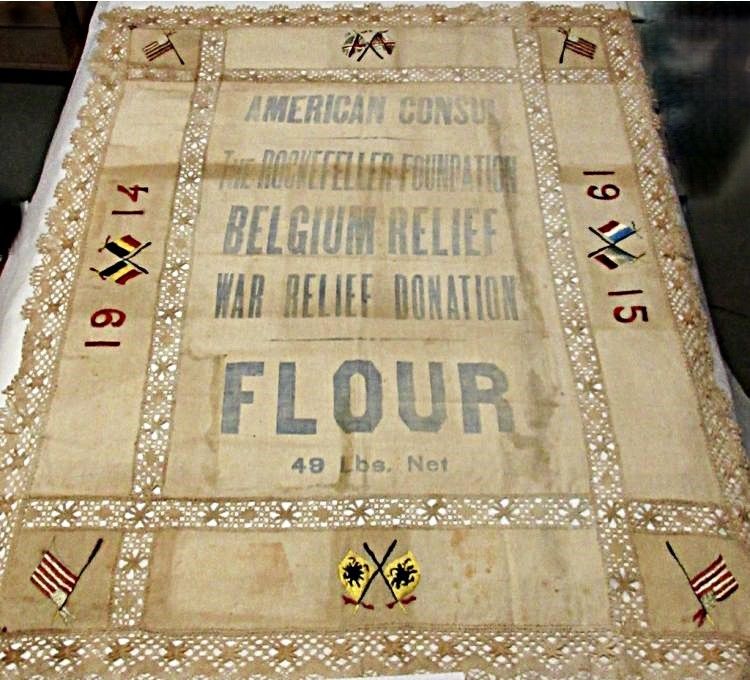

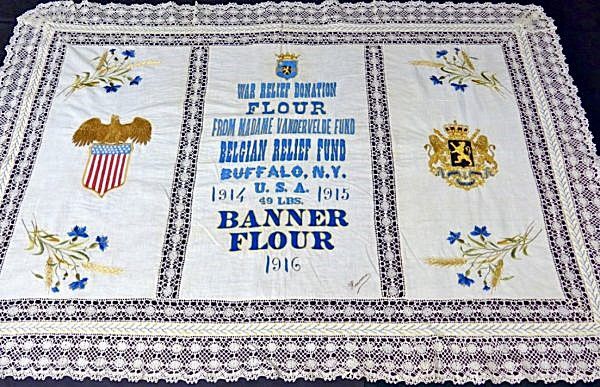

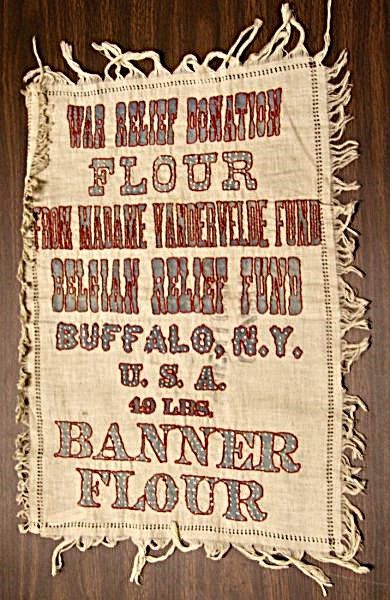

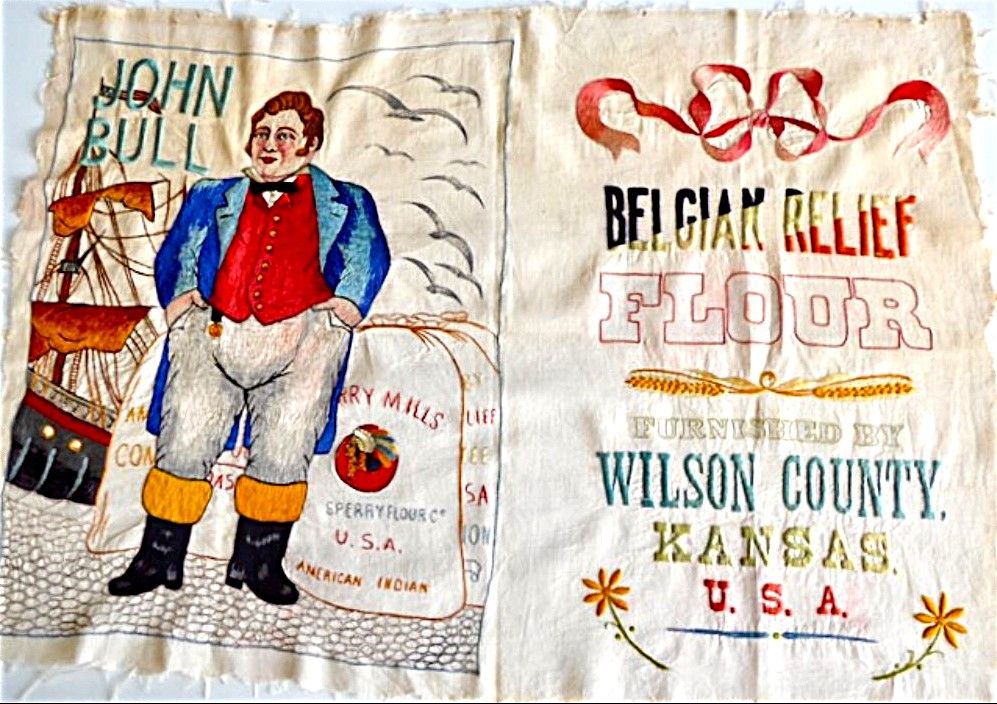

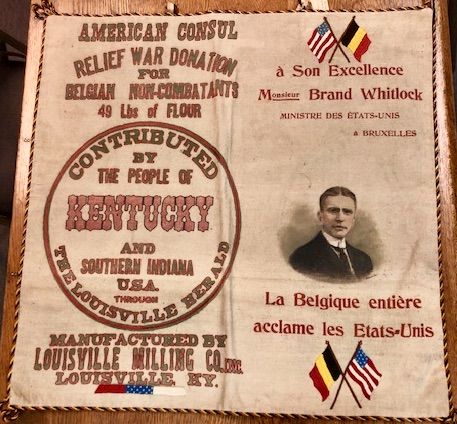

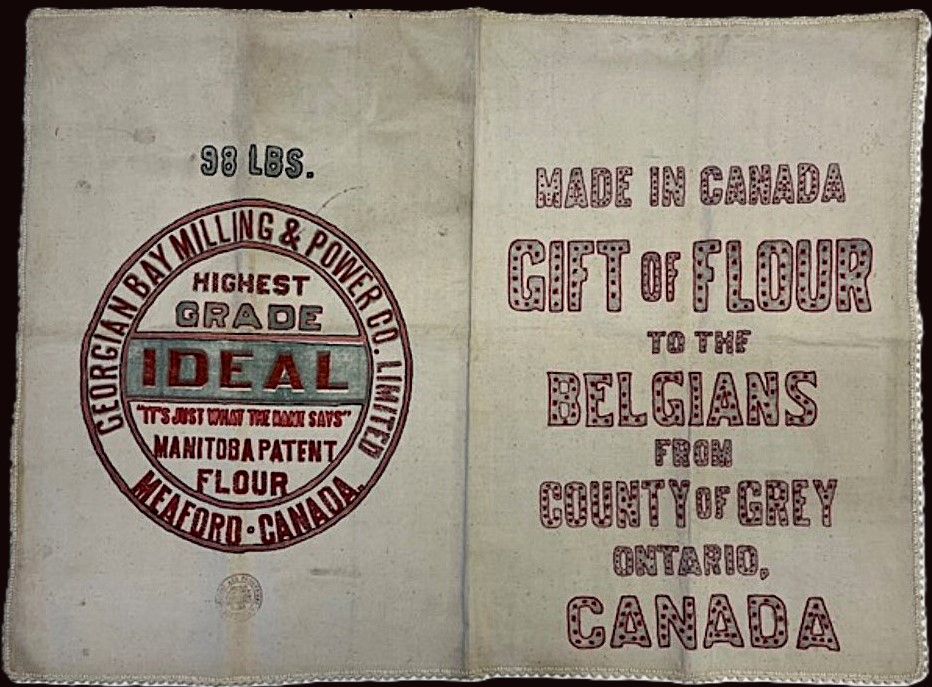

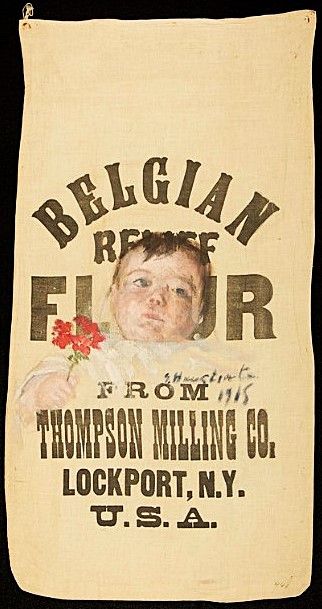

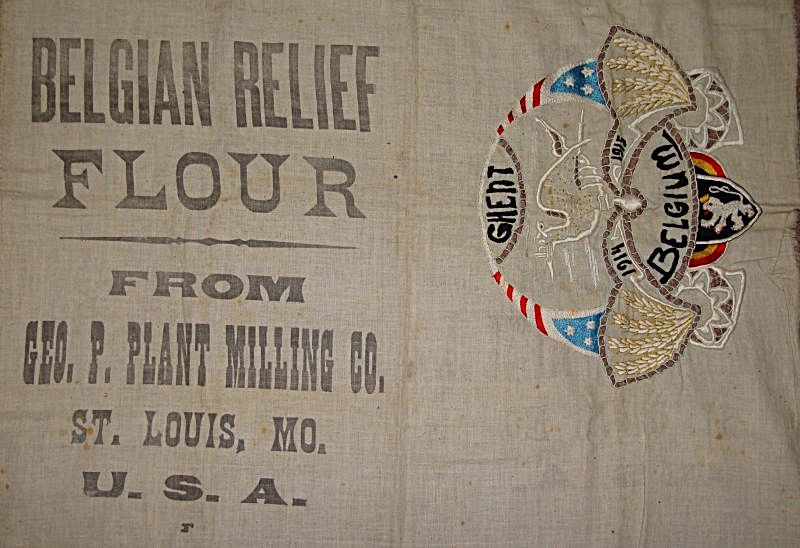

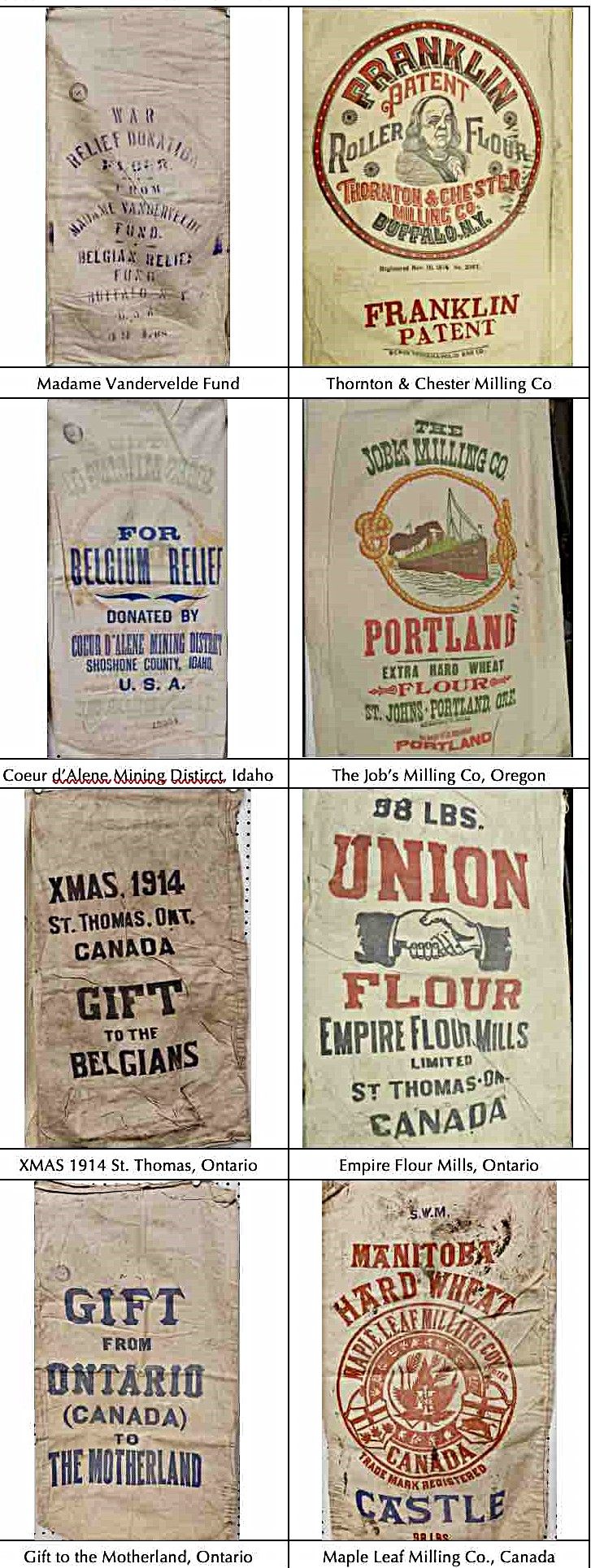

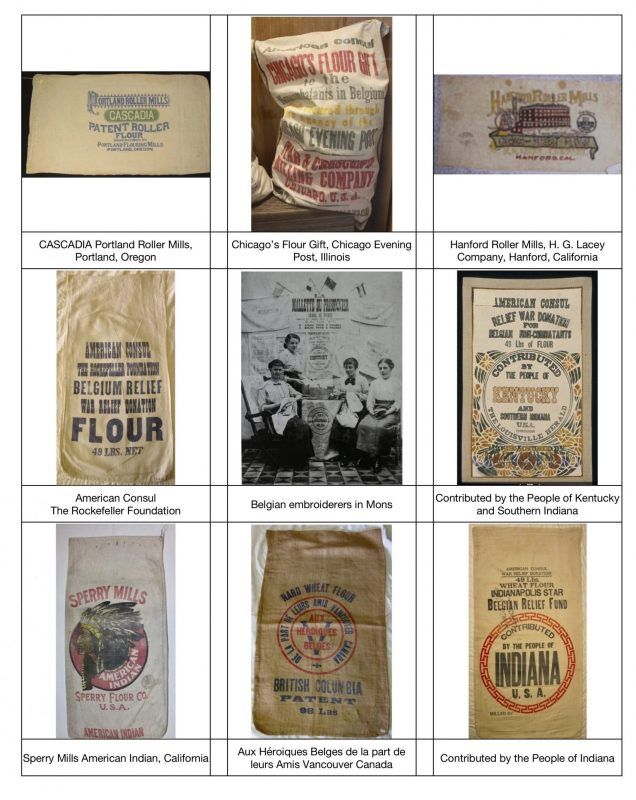

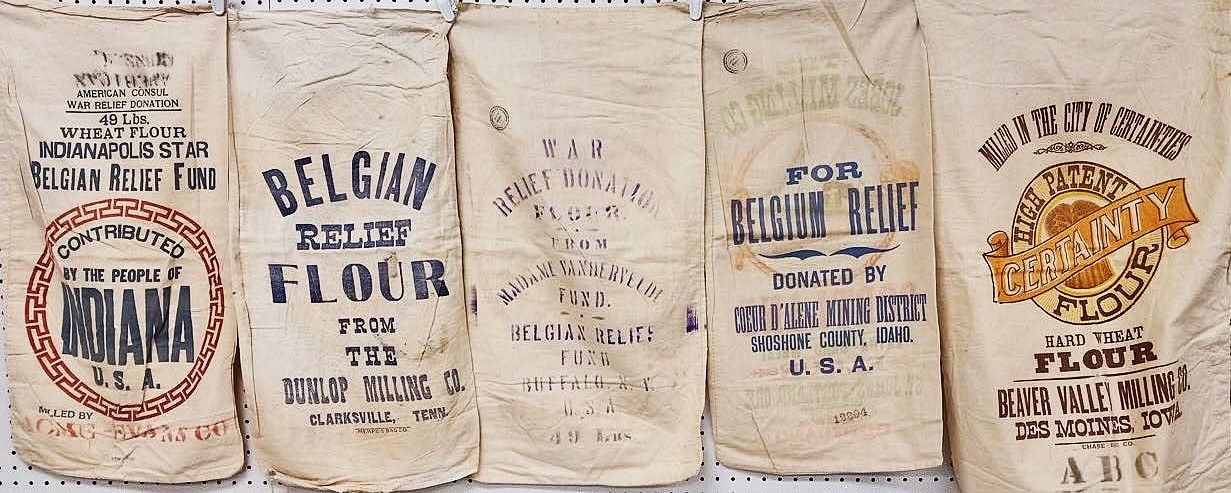

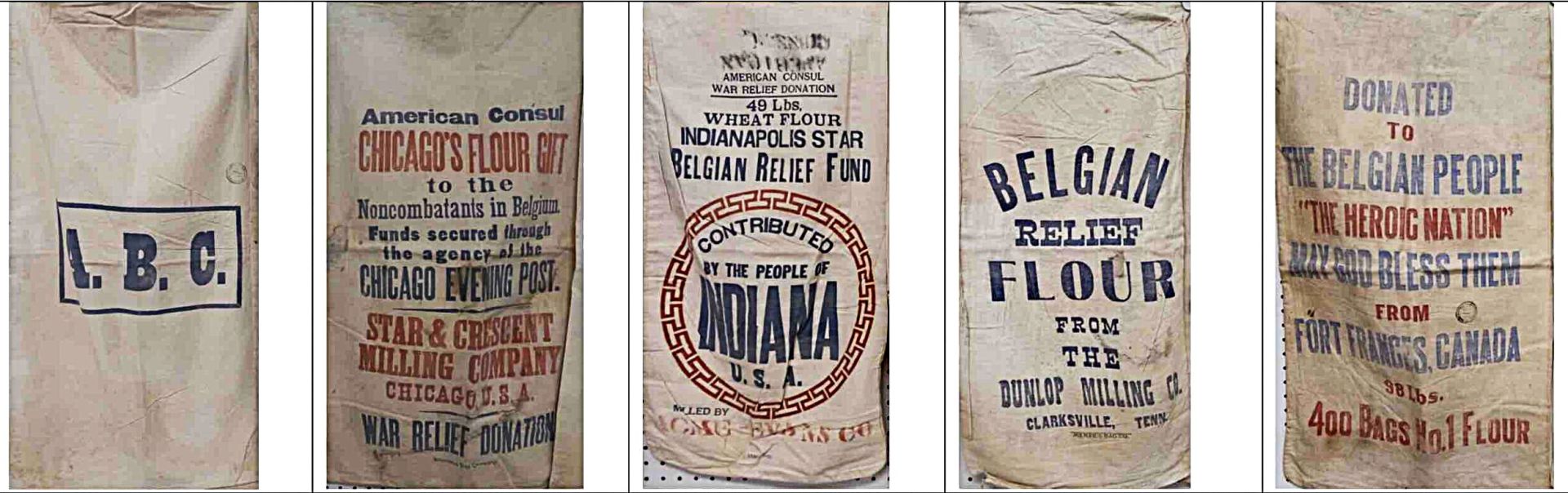

The CRB's aim was to provide food relief for war-torn Belgium, and eventually 5.7 million tons of food was shipped. Flour with other grains and sugar were sent in cotton sacks, and distributed by the Comité National de Secours et d'Alimentation.

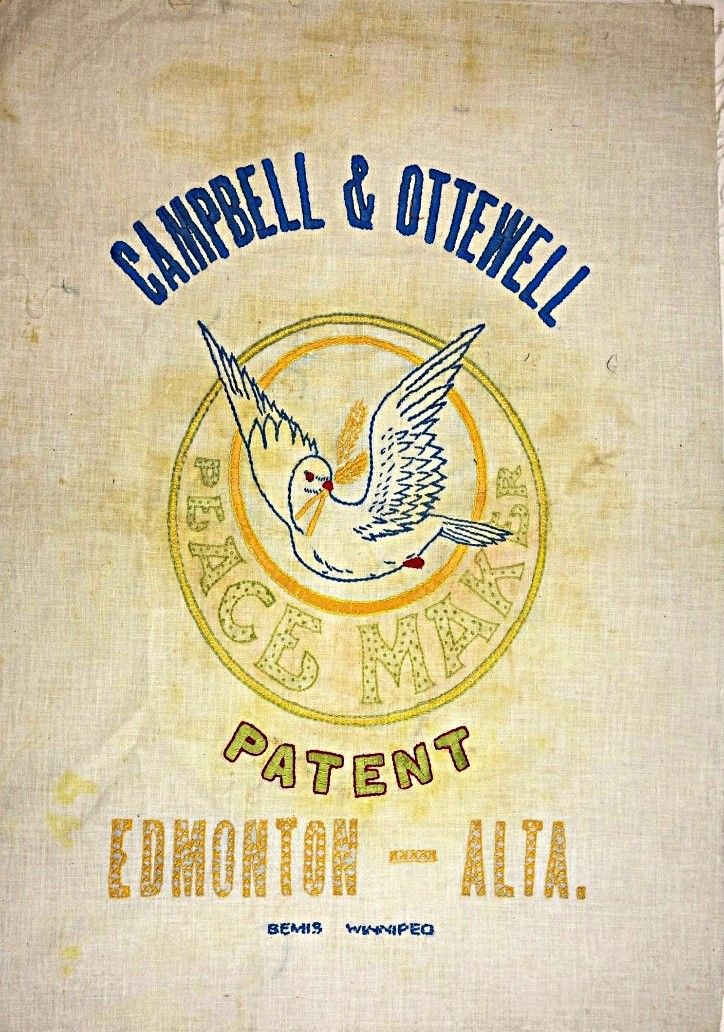

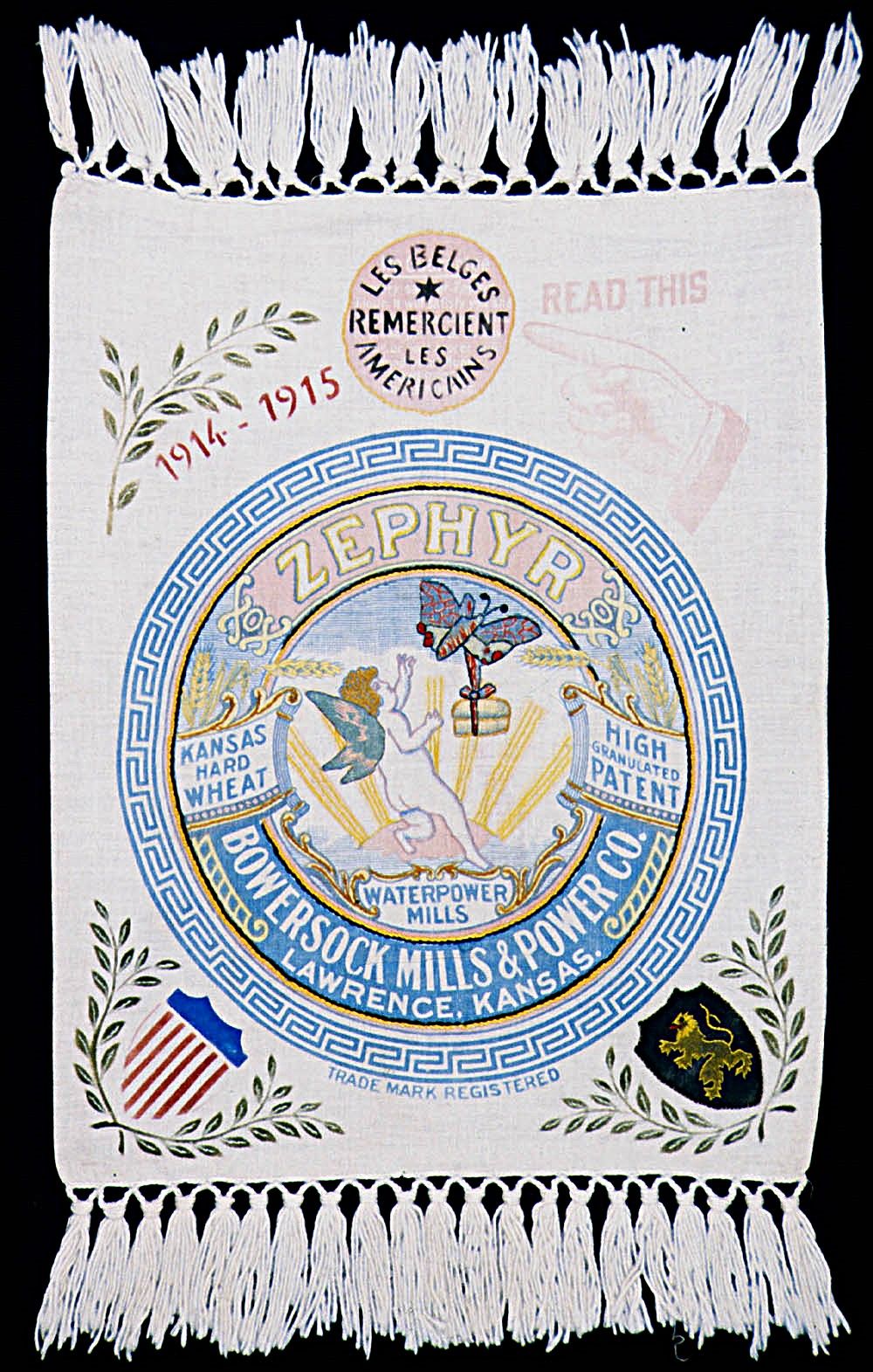

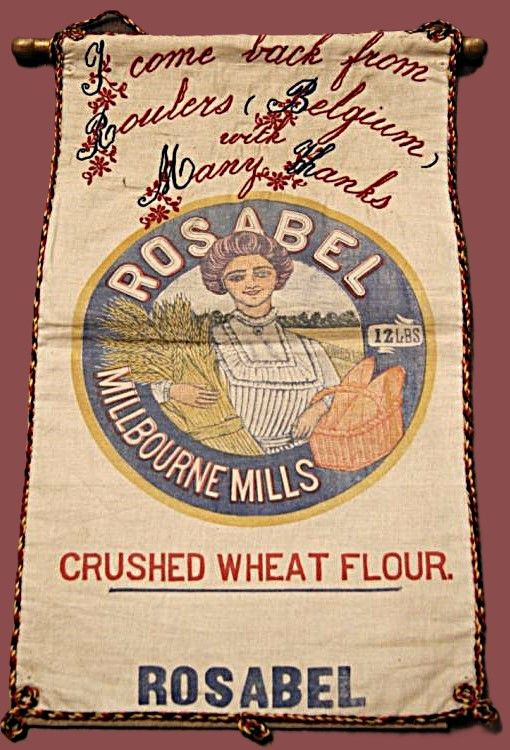

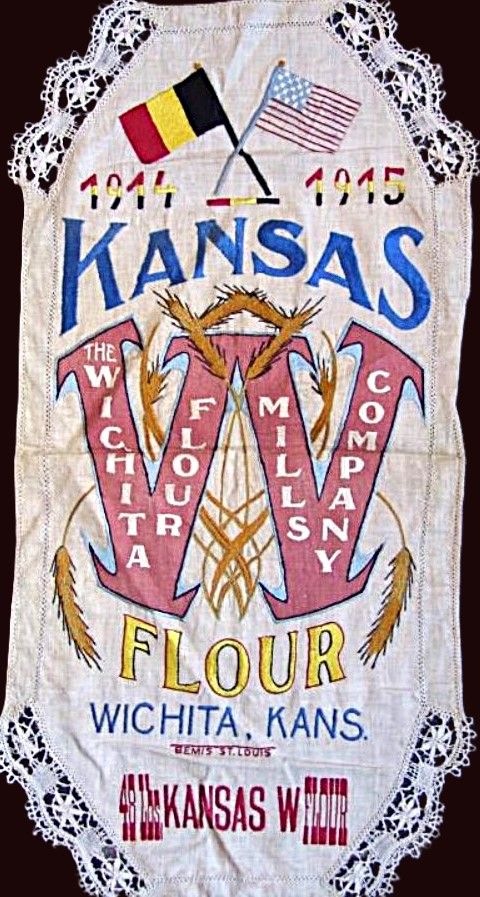

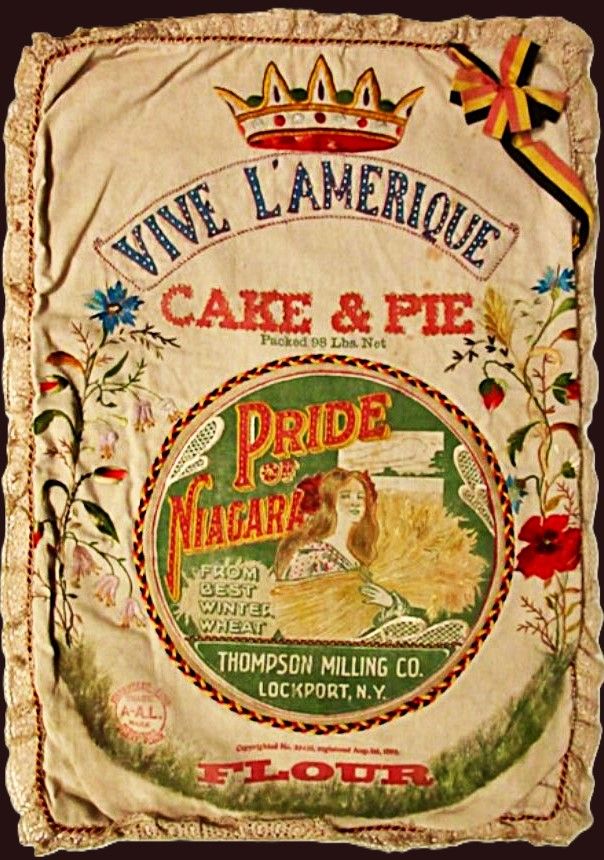

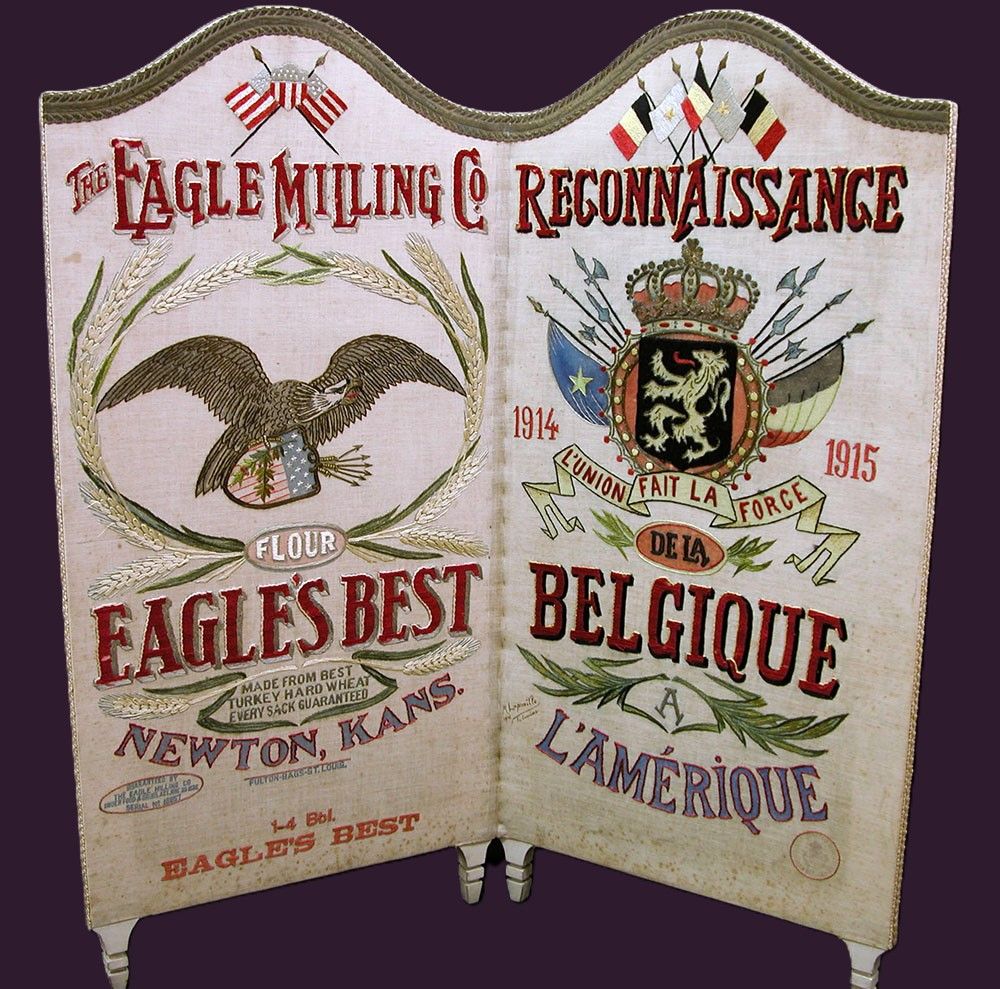

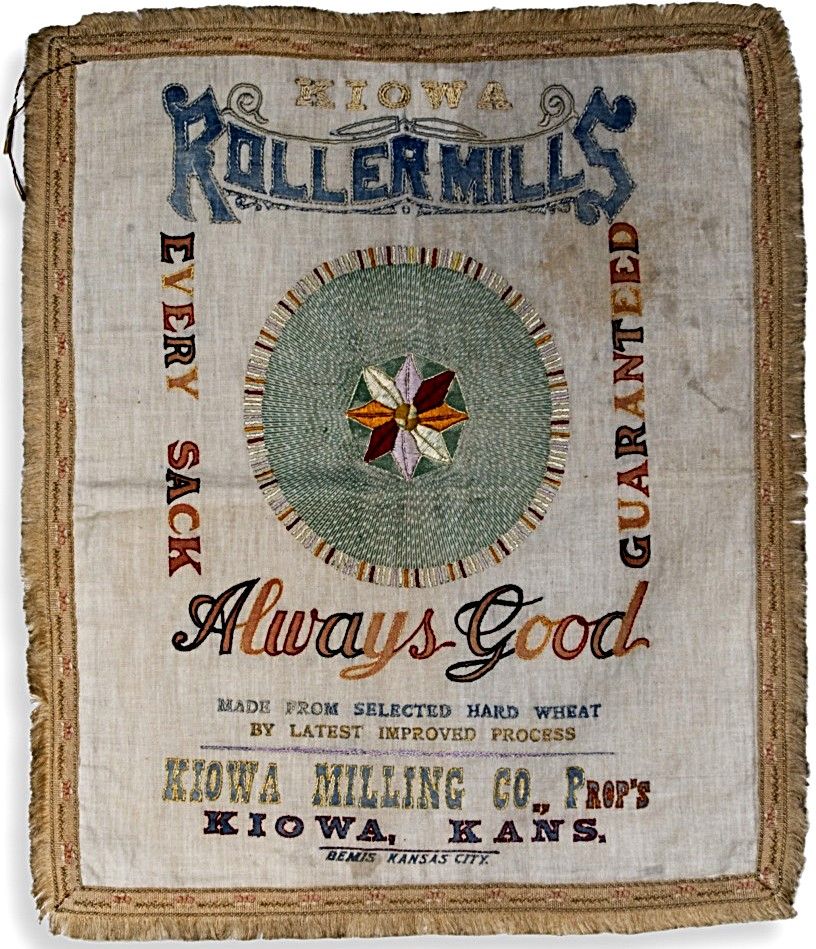

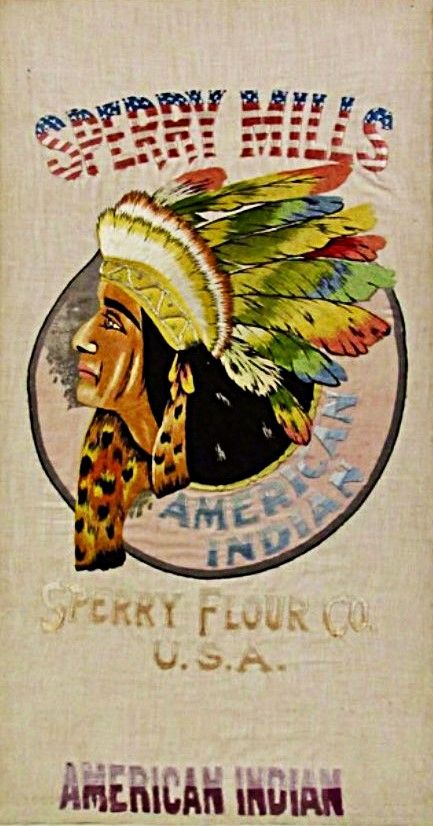

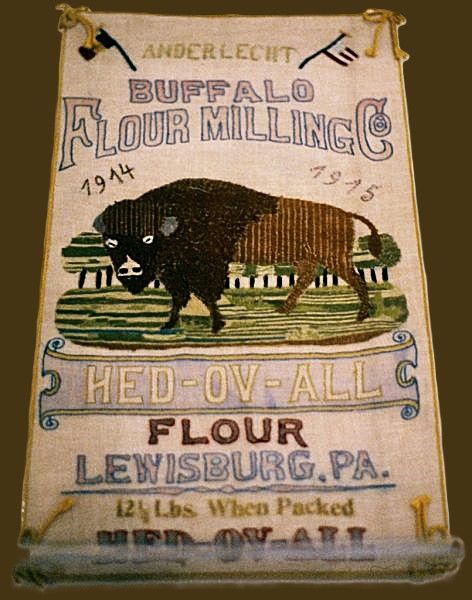

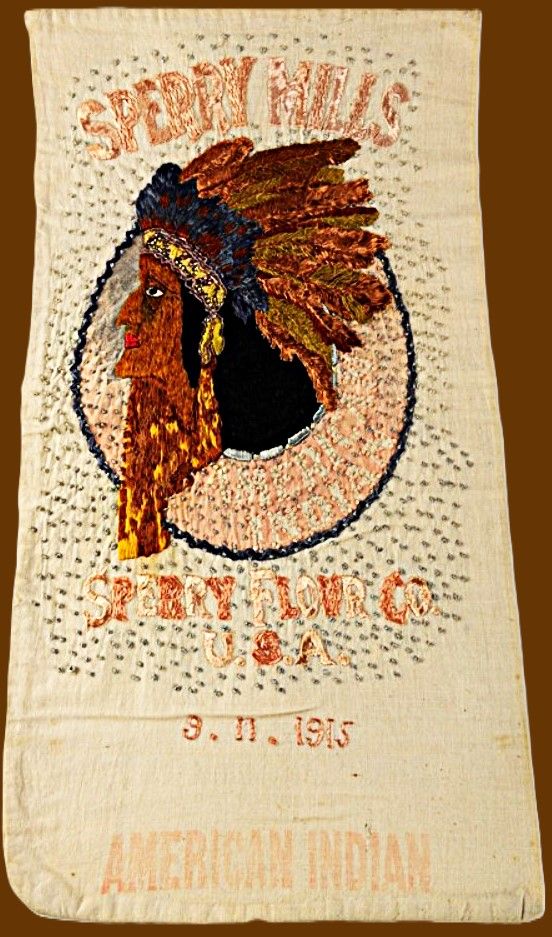

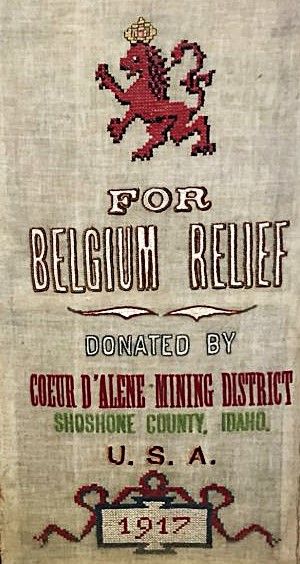

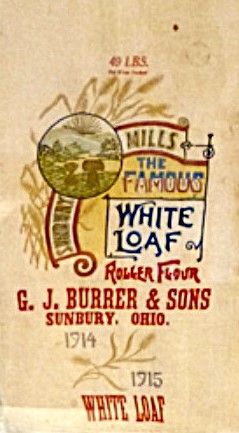

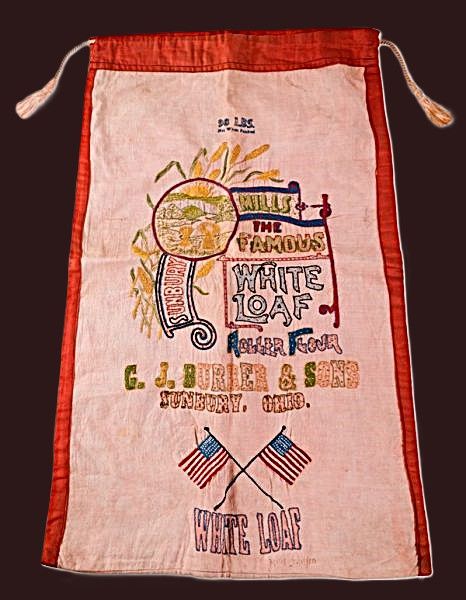

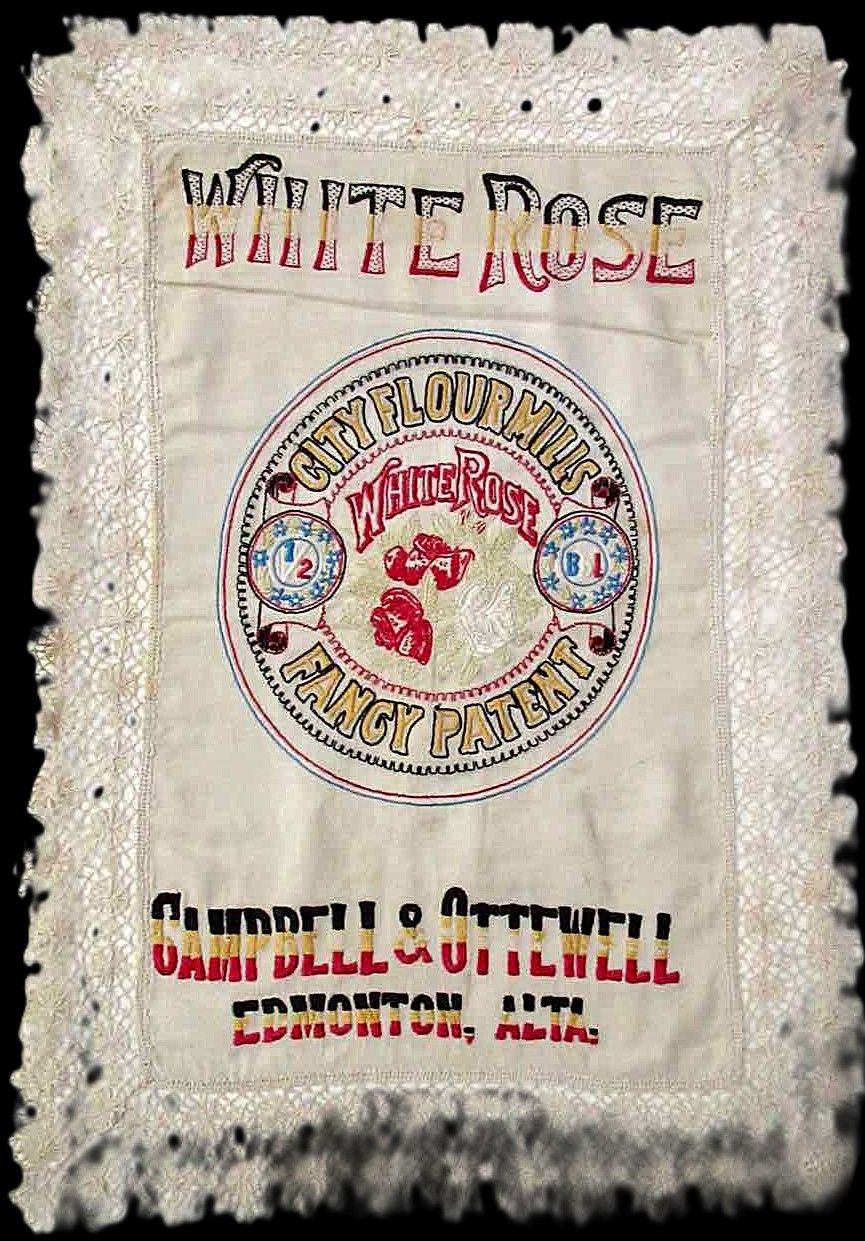

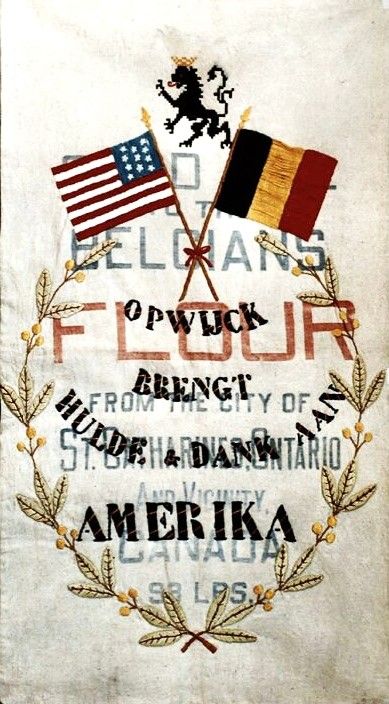

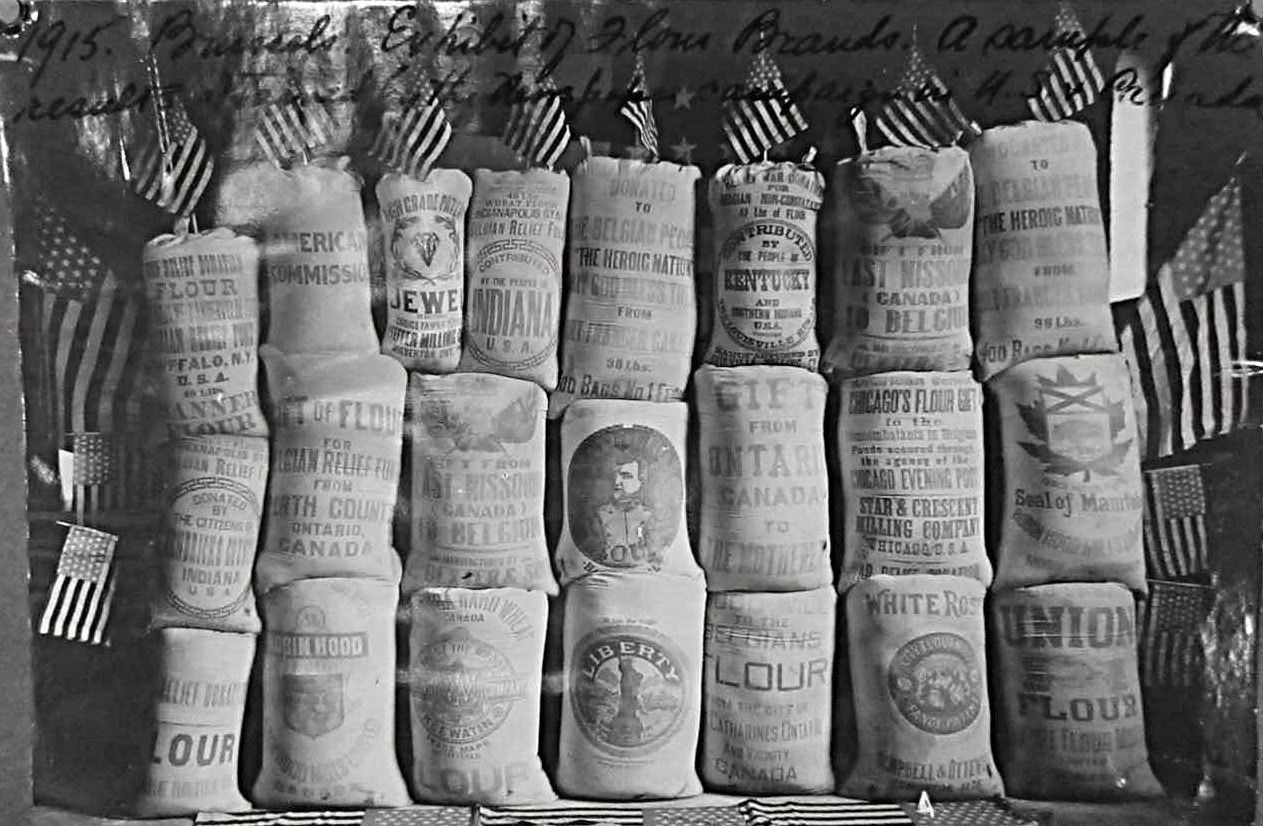

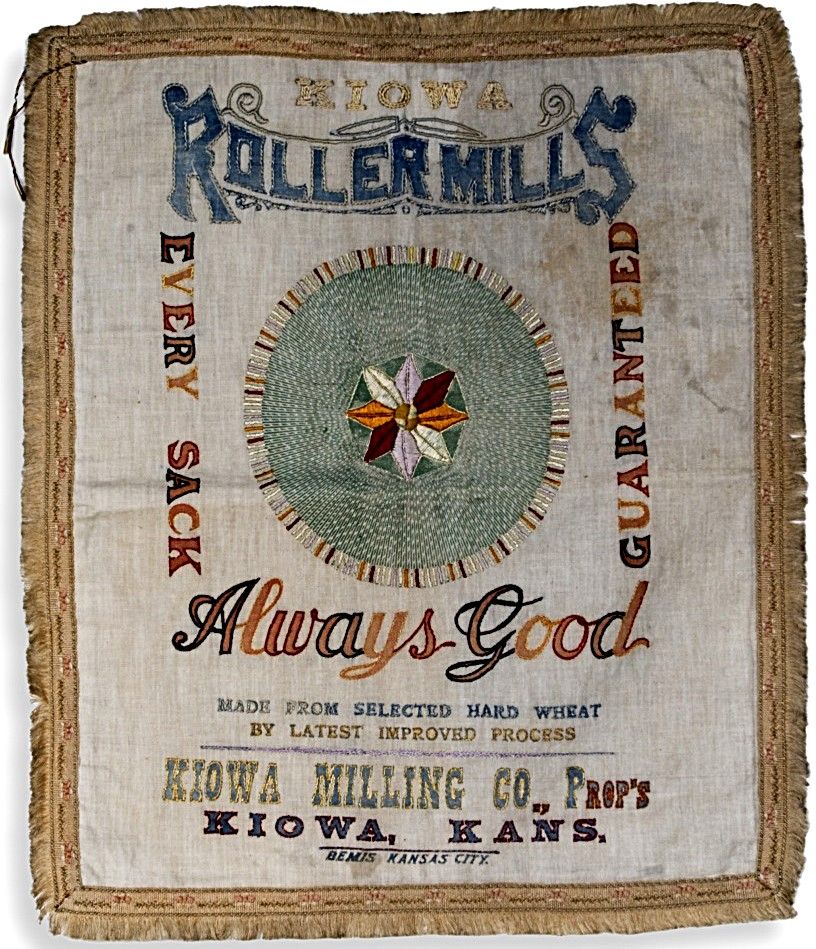

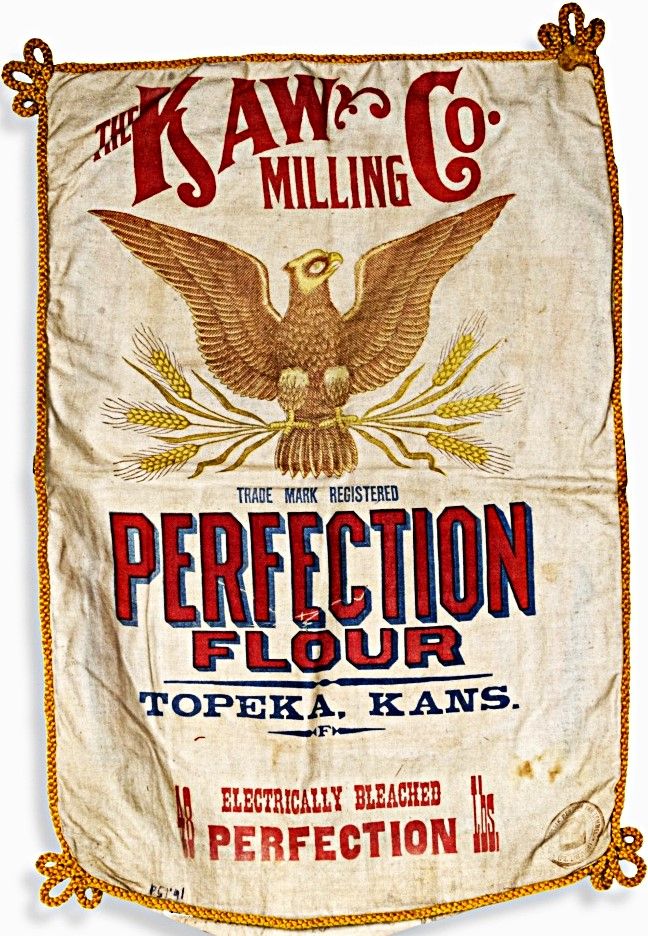

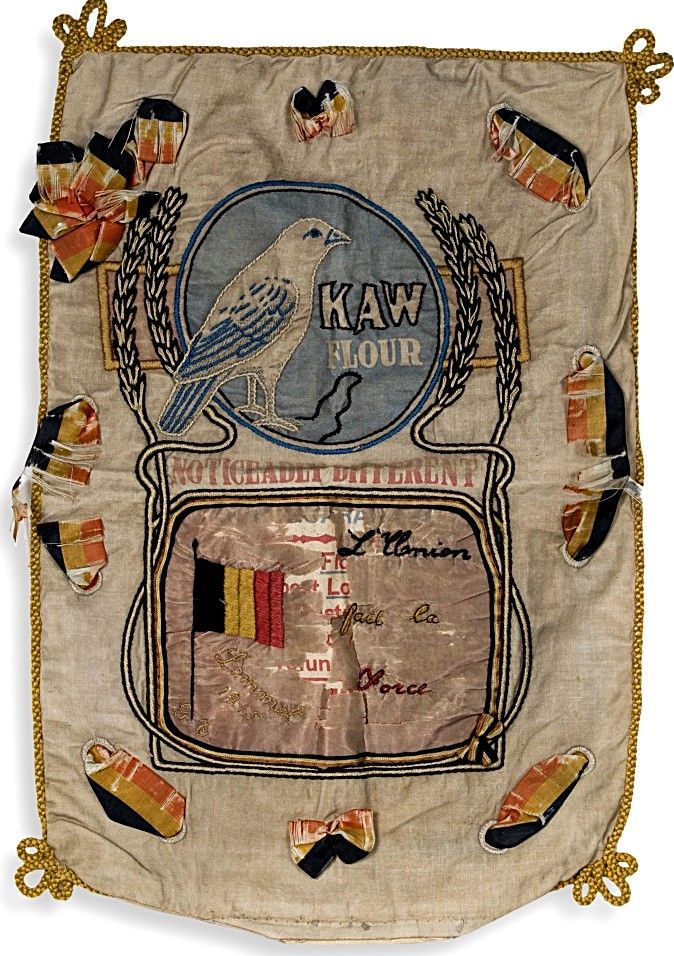

The flour sackss were filled by various American and Canadian mills and were often printed with their names and logos. They were sent to neutral Rotterdam (The Netherlands) and from there they were distributed to German-occupied Belgium.

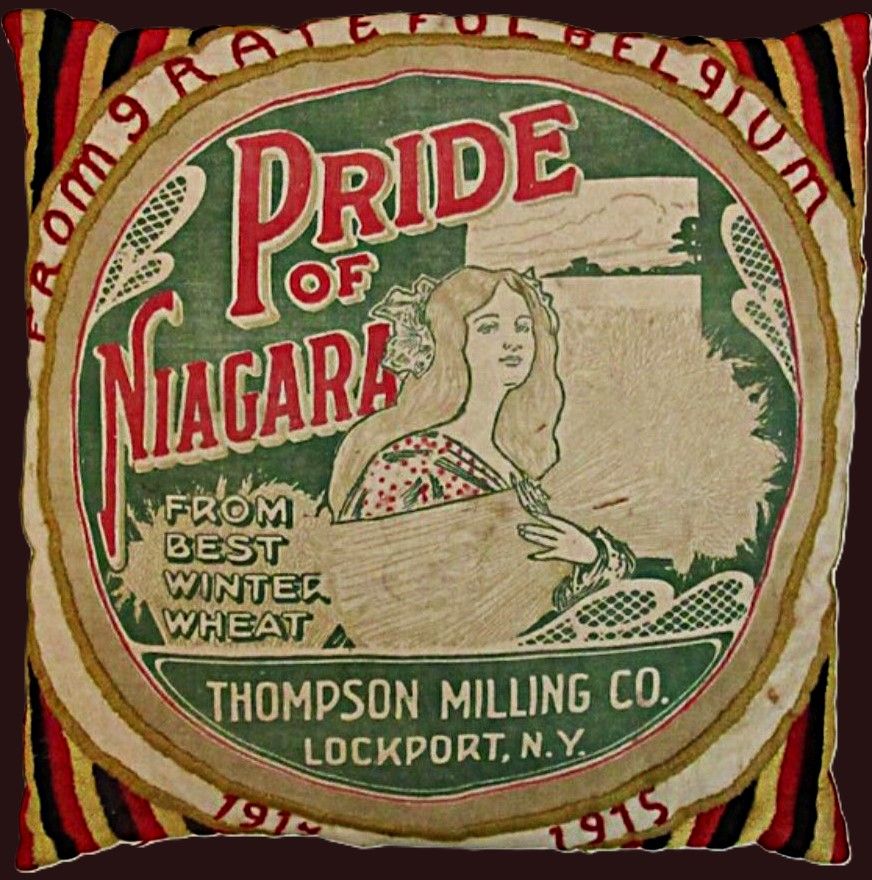

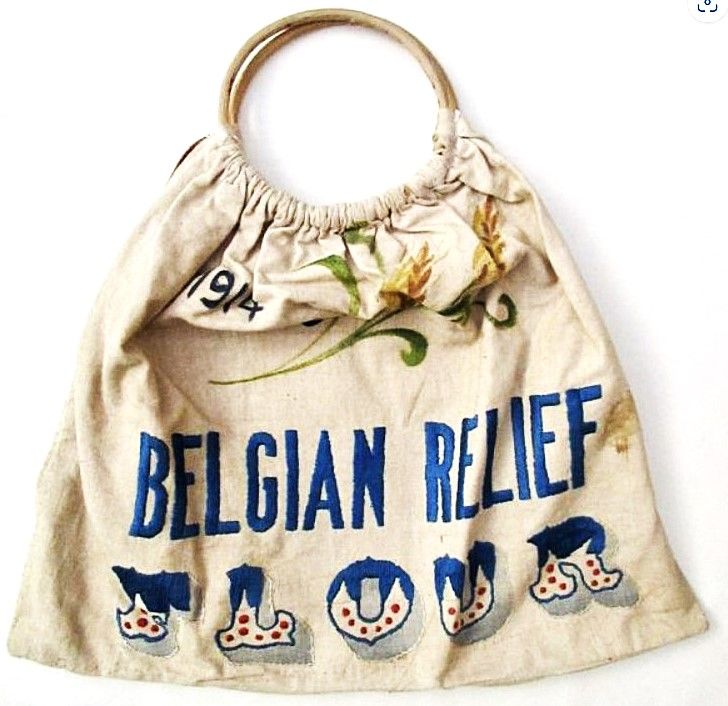

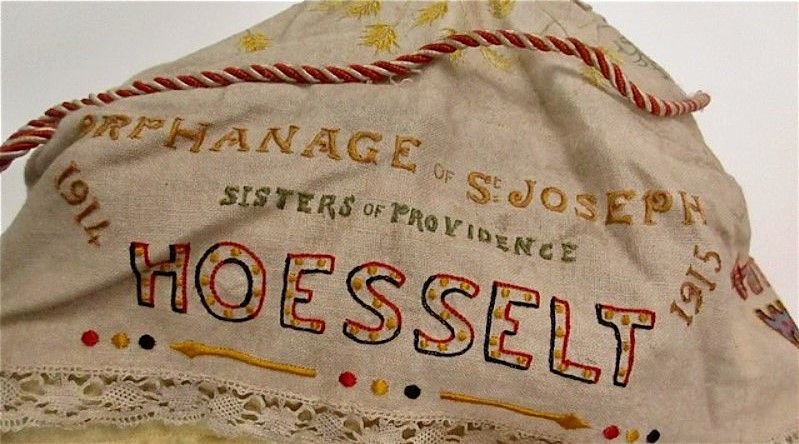

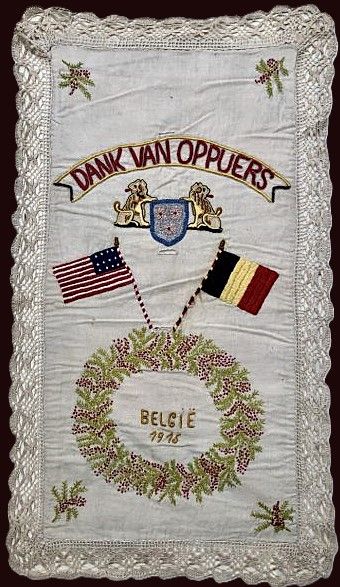

The CRB also collected the empty flour sacks and distributed them to convent workshops, schools, sewing workrooms in general, as well as individual artists. Professional schools trained women to sew, embroider textiles, and make the famous Belgian lace. Large sewing workrooms were established in Belgian cities to provide work for thousands of unemployed. The flour sacks were made into clothing, accessories, pillows, bags, and other functional items. Many of these centres were based in large urban centres, such as Antwerp and Brussels, and provided work for thousands of girls and women.

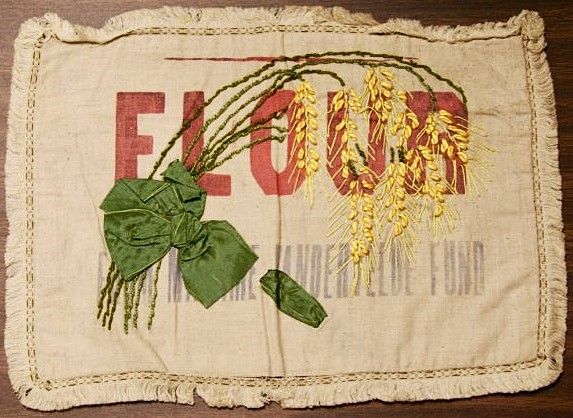

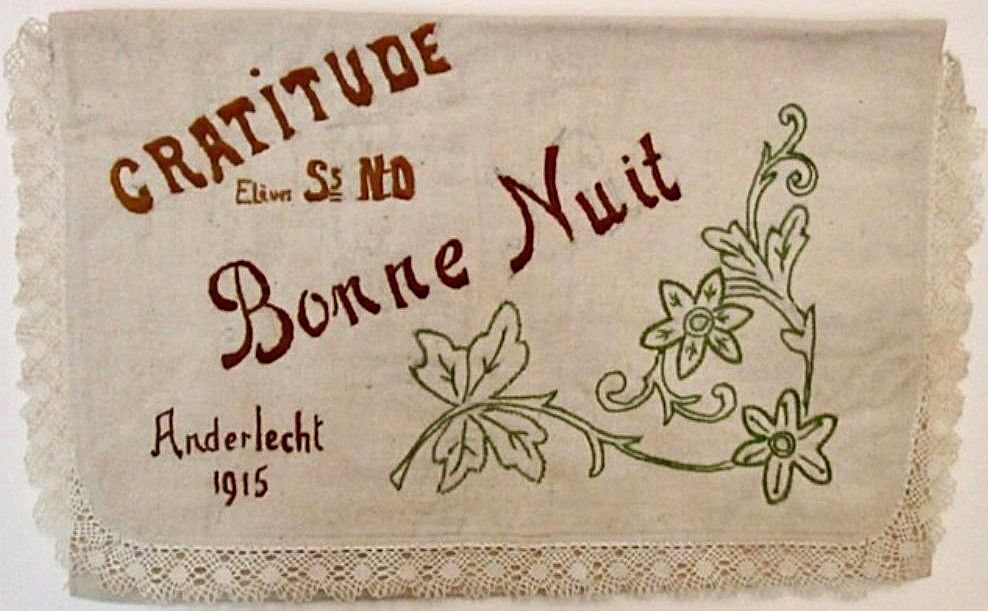

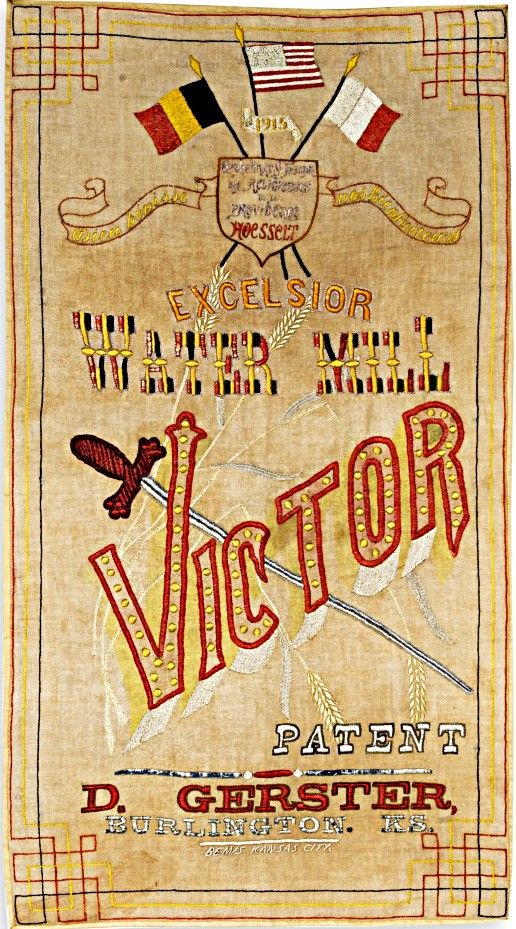

Many women worked their embroideries over the mill logo and brand names, but others left the original designs visible and used embroidery to enhance the appearance of the bags. Many embroiderers also stitched their names and/or messages onto the flour sacks. The Nuns of Providence, of the St. Joseph Orphanage, for example, embroidered their vocation on one sack along with the motto, "Dieu bénisse nos Bienfaiceurs" ('God bless our benefactors').

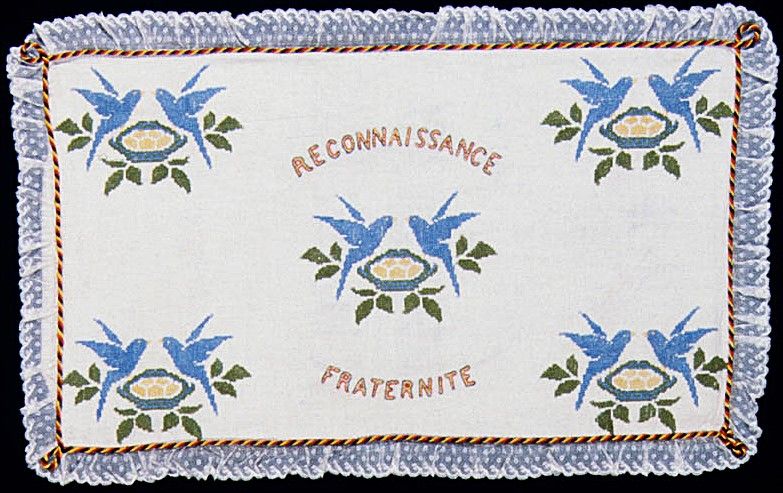

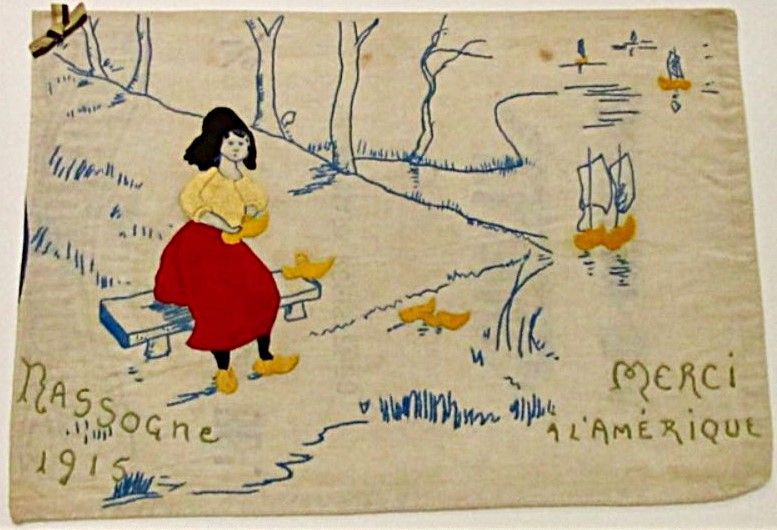

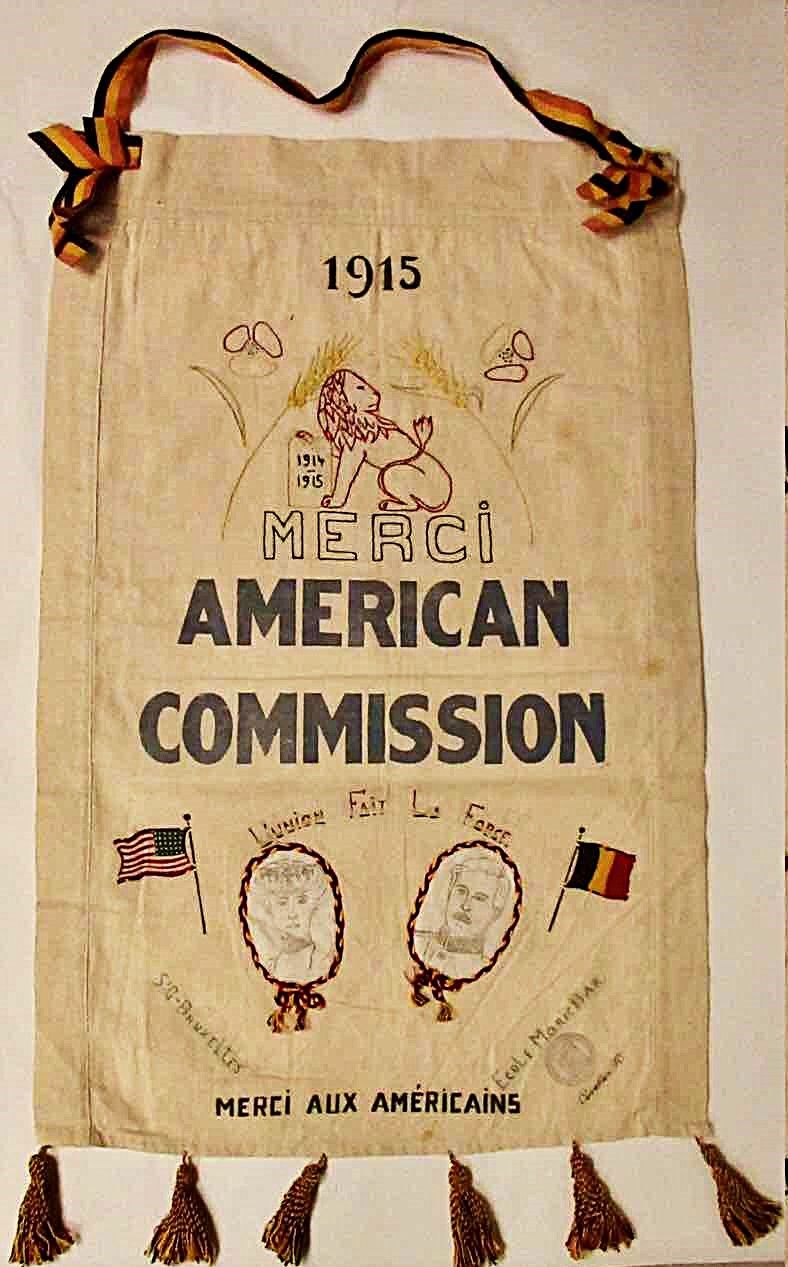

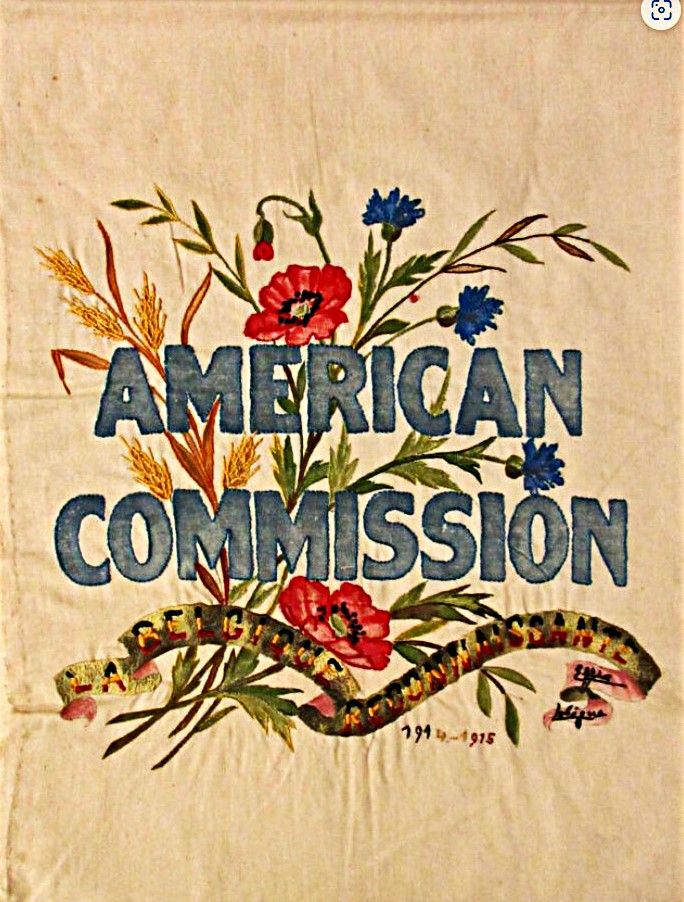

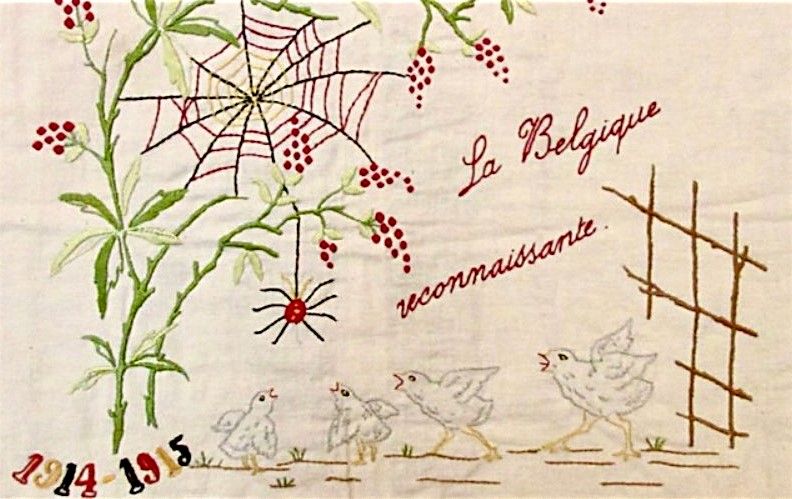

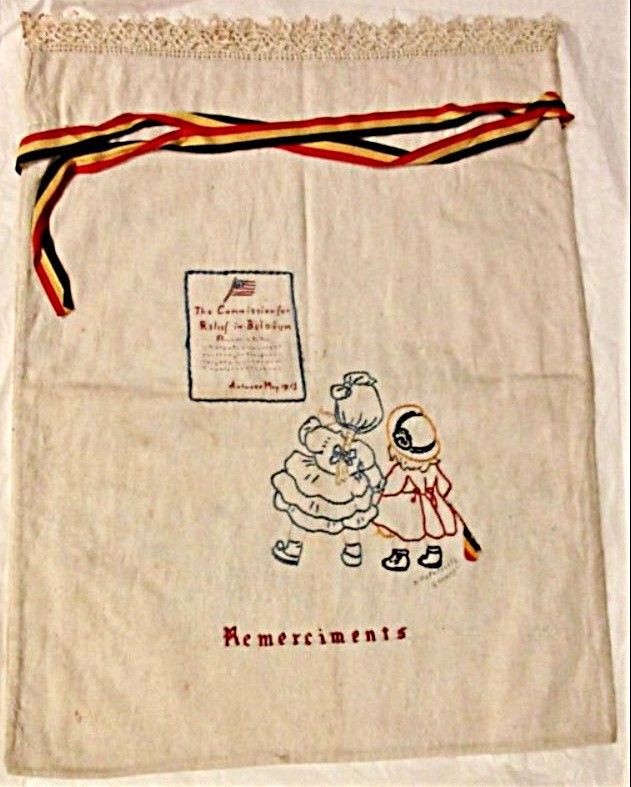

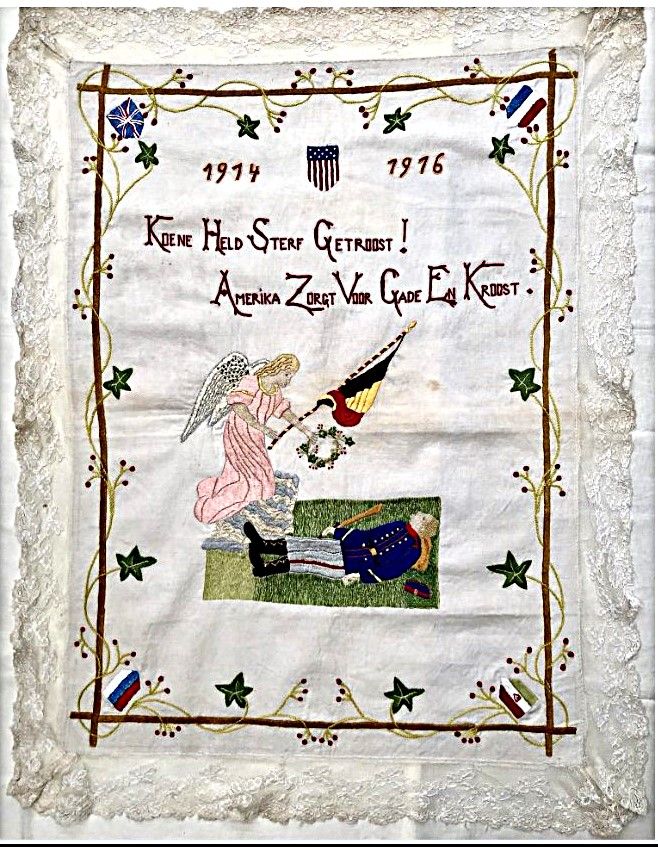

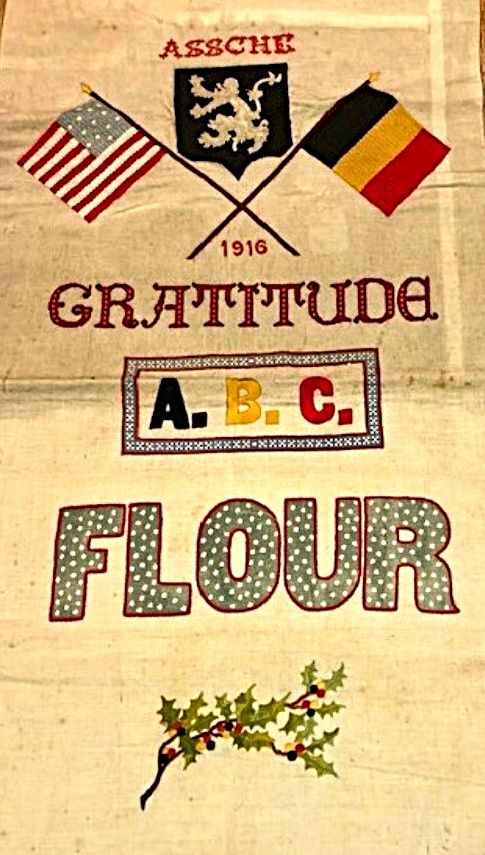

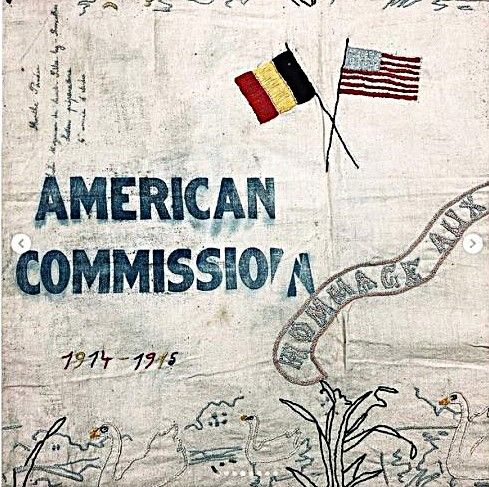

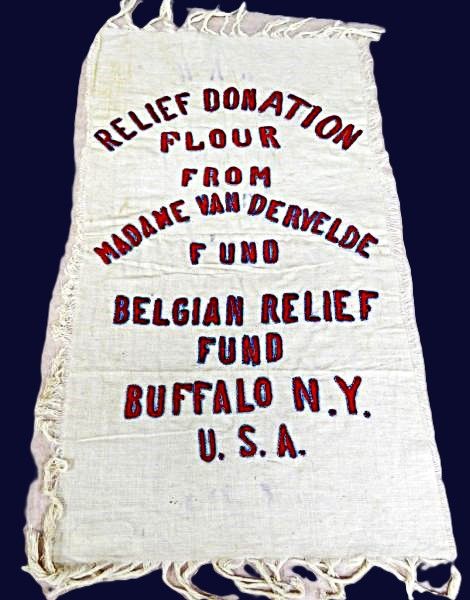

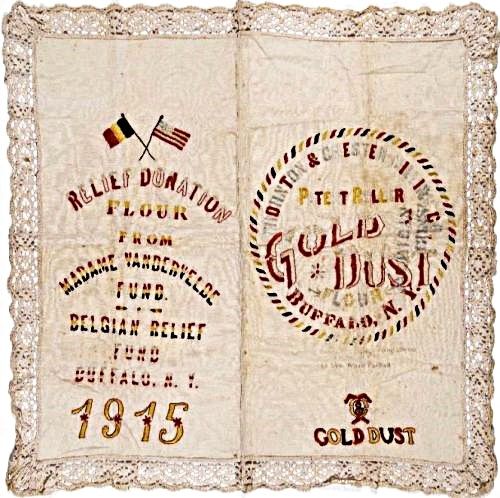

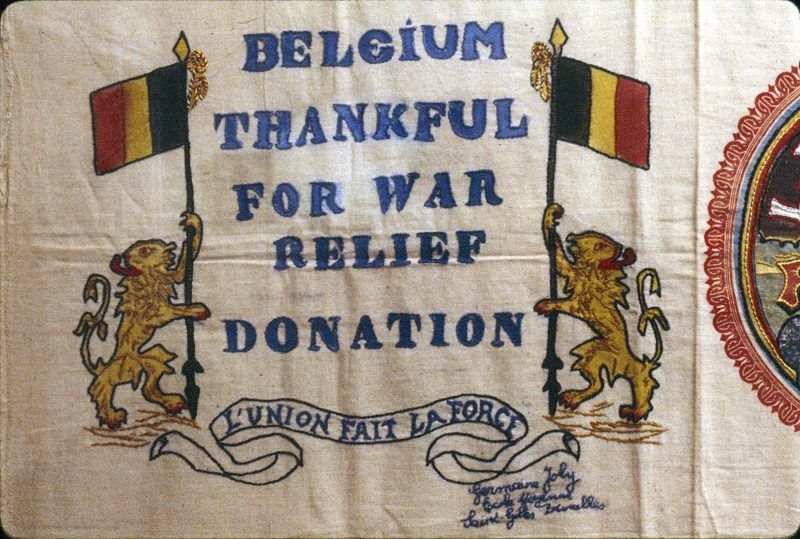

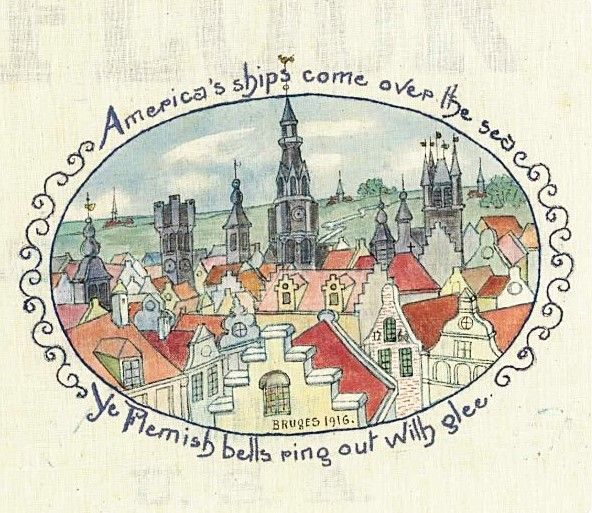

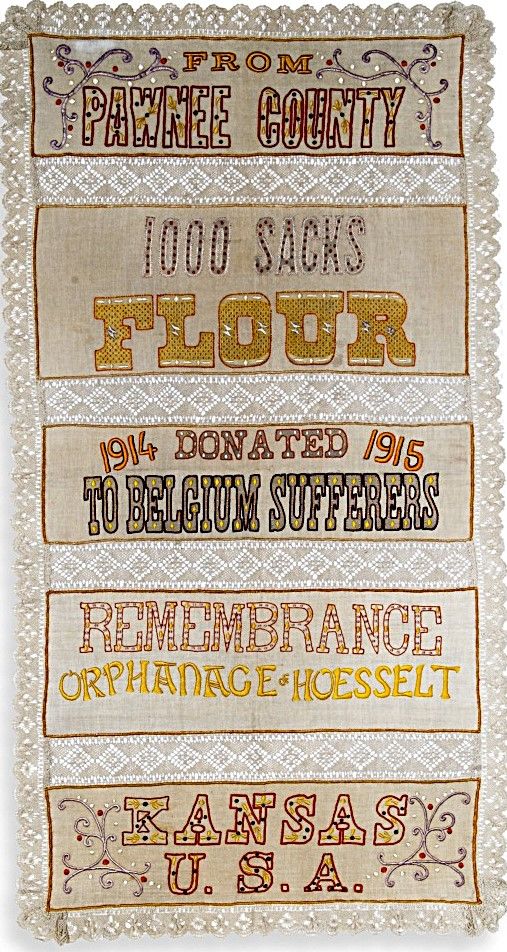

Some chose to embroider original designs on the sacks and then embroidered, painted, or stenciled on the fabric. Design elements included: messages of gratitude, lace embellishments, Belgian and American flags, lions, roosters, eagles, and symbols of peace. Some artists used the sacks as canvas for oil paintings.

The embroidered flour sacks were distributed to organizations in Belgium, England, and the United States, and then sold to raise funds for food relief and to aid prisoners of war. Some were given as gifts of gratitude to members of the CRB. Herbert Hoover was given several hundred of these decorated flour sacks as gifts. The Herbert Hoover Presidential Library-Museum has one of the largest collections of WW1 flour sacks in the world.

Two sets of embroidered sacks (and messages) can be distinguished, namely those that were worked by Flemish (Dutch) speakers from the north of the country and those by Walloon (French) speakers in the south. Many of these sacks were sent back to Allied countries, especially Canada and the USA, as souvenirs.

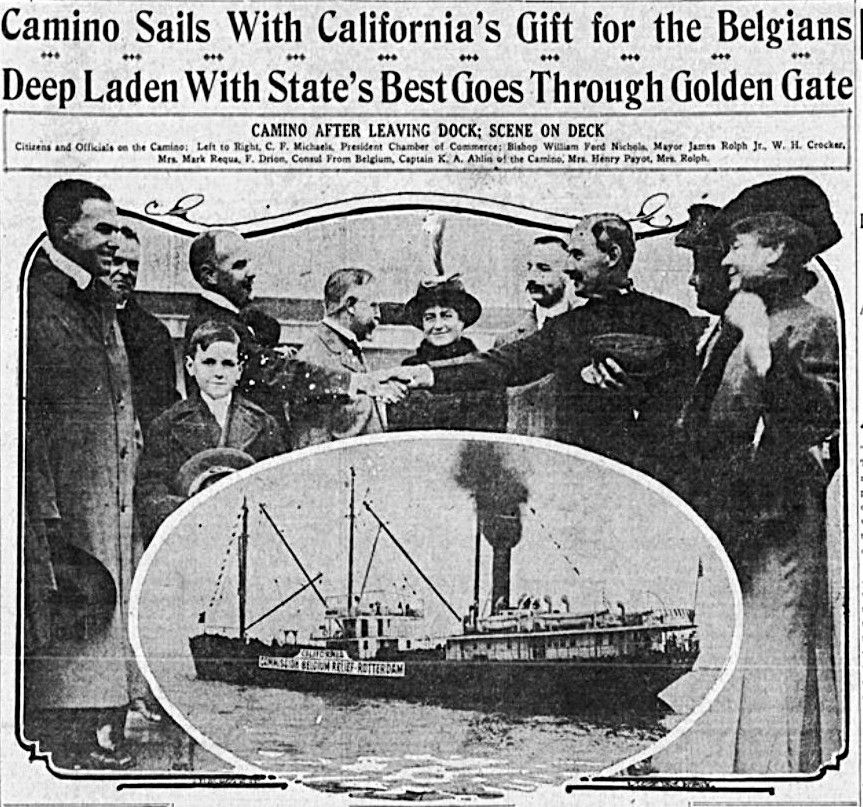

Kansas was one of the most active states responding to the CRB's pleas. Noting the bumper wheat crop of 1914, former Kansas Governor Walter Stubbs rallied Kansans with the slogan, "[From] Kansas, the greatest beneficiary of the war, to Belgium, the greatest sufferer of the war" (Kansas farmers benefited from higher grain prices due to increased wartime demand). By November 1914, Kansans had donated 50,000 barrels of flour to the CRB. Pawnee County alone sent 1,000 sacks, while Burlington residents raised $600 for the purchase of foodstuffs. Some milling companies contributed both money and flour. All told, the state's donation filled the hold of the ship Hannah, which set sail for Belgium the following January. The New York Times described the scene on the docks: "From the aftermast of the ship fluttered the flag of Kansas, while a great streamer that stretched half way around the ship bore the single word 'Kansas'."

After the ship left New York harbor, the CRB monitored its progress through perilous waters where German U-boats might mistake it for a combatant. When the vessel landed in neutral Rotterdam, the cargo had to be unloaded and conveyed to Belgium. Once inside that country's borders, the flour had to be prepared into comestibles and distributed to a hungry populace. The CRB's volunteers repeated this process over and over again for every ship that crossed the Atlantic during the war.

Once in Europe, the rather ordinary cotton sacks containing the donated flour caught the attention of both the Allies and Central Powers. One concern was that the Germans would use the cotton in their munitions plants. Therefore, the CRB controlled even the distribution and location of the flour sacks. Many sacks were recycled into clothing and household items, but some were turned into objects of beauty. Over-stitching the printed mill stamps with colorful silk floss, and adding original designs of their own, Belgian women used their needles to pay a debt of gratitude to those who fed them. They returned the decorated bags to benefactors in the United States.

The Kansas Belgian Relief Fund first began receiving embroidered sacks a year after the Hannah had sailed, in early 1916. In an article noting that the embroidered sacks would be displayed in a downtown store window, the Topeka Daily Capital described the workmanship as "beautiful" and illustrative of "the wonderful talent of the Belgian women and girls, who are world-famous for their laces and embroidery. It is done on the ordinary sacks in which Kansas millers ship their product, and this makes the work even more remarkable."

A few embroiderers of the Kansas sacks are known by name—for example, Gabrielle Tournier and Madame Jean Noots—because they attached cards to their work. The Nuns of Providence, St. Joseph Orphanage, embroidered their vocation on one sack along with the motto, "Dieu bénisse nos Bienfaiceurs" (God blesses our Benefactors). An anonymous needleworker expressed "Merci á l’Amerique" (Thank you, America) on a sack embellished with silk ribbon and delicate lace.

Shops decorated their windows with souvenirs made by the Belgians from sacks of flour sent to them by the Belgian Relief Committee,

and sold to raise money for the Belgian people.

(Below) Various examples of Flour Sack Art